1. The Problem

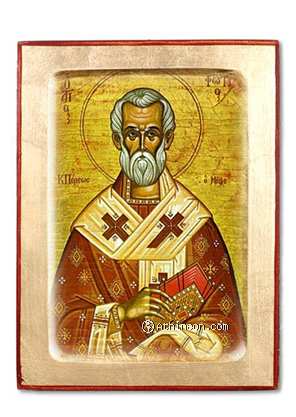

Have you ever noticed that on certain icons, the persons depicted, though they seem to be looking at you, are in fact looking away from you? (fig. 1)Christ, the Mother of God, or the saints have their faces turned directly to the viewer, but, either slightly or very obviously, they are not engaging in eye-to-eye contact. (fig. 2) I am not referring, to festal and other event-oriented icons, for example, that of the Forty Martyrs of Sebaste, whose purpose is principally to make present persons “in an event.” Icons, such as those of the Mother of Tenderness, the Deisis, or St John the Theologian in meditation, though they are person-oriented, are not strictly intended to draw us into a direct personal communion with the persons depicted.

Are the saints in some icons avoiding eye contact by accident or on purpose? Do iconographers paint them this way for a reason? If so, what reason? Whether icons are painted this way by accident or on purpose, the question of eye contact in icons is an important one.

2. The Psychological Background

About an hour later another man insisted saying, “This fellow was certainly with him. Why, he is a Galilean.” “My friend,” said Peter, “I do not know what you are talking about.” At that instant while he was still speaking, the cock crew, and the Lord turned and looked straight at Peter, and Peter remembered what the Lord had said to him, “Before the cock crows today, you will have disowned me three times.” And he went outside and wept bitterly. (St. Luke 22:60-62)

From this passage, and from our own experience, we know the importance and power of a look: “If looks could kill…” In everyday life, eye contact is a vehicle for so much communication; it accompanies verbal as well as non-verbal communication. A public speaker can live or die through eye contact. We are ill at ease when certain people look us right in the eye; we sense the presence of someone or something we do not want to be close to. Lovers penetrate into each other by prolonged eye contact. It is commonplace that the eyes are a gateway into the soul, into the mystery that is the human person. We not only receive others into ourselves through our eyes, but we also display ourselves to others in the same way. Our eyes are like a TV screen onto which we project our inner selves. If eye contact with another person is broken for some reason or purposefully avoided, we immediately feel a loss of contact, a loss of presence, and communication is impeded. Nothing is more unnerving than for someone to speak to us and never look us straight in the eye. Have you ever talked to someone wearing sun glasses?

3. The Doctrinal Background

[A man who robbed churches confesses…] Once I broke into a church where there was a miraculous icon. I went up to this image in order to take advantage of what I thought would be an easy take. At that moment, I looked at the Christ-Child and was glued to the floor, petrified. A few minutes later I tried again to extend my hand toward the image but for the second time, the Christ-Child paralyzed me by his look. Oh well, I thought, a bungled job…[1]1

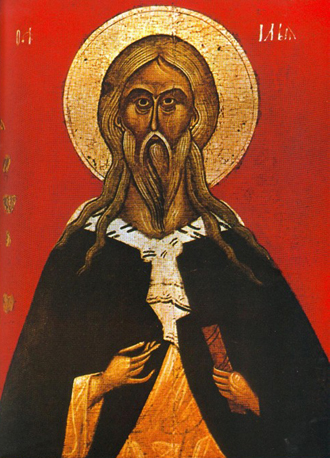

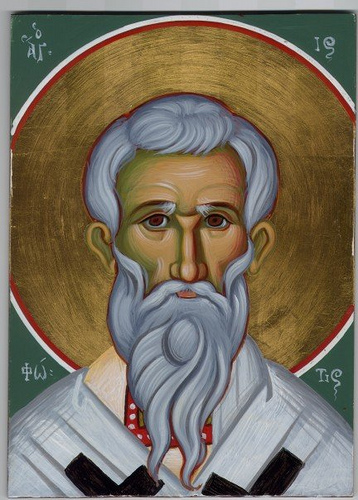

In his book The Art of the Icon: A Theology of Beauty[2]2, Paul Evdokimov has a chapter on the “Theology of Presence.” In this and other chapters, the author sets out what we know to be one of the purposes of Orthodox icons, namely to make present the person or persons represented in the image. The person’s presence in his image is at the heart of the theological vision which undergirds the Orthodox Church’s experience of icons. Among other things, we read in many sources that the eyes of the saints painted on icons are larger than in natural life to emphasize that personal presence which is carried by and through the eyes. (figs. 3-4) Other artistic techniques, such as inverse perspective, are used to enhance the feeling that the persons painted in icons are looking at us, addressing us, and penetrating us by their looks. How many people do not like icons or do not want to look at them, not for esthetic reasons, but because they are unnerved by the penetrating look of holiness coming at them through the saints’ eyes? And this is, of course, the whole purpose of those penetrating looks: to draw our attention to the impurities, sins, and darkness in us, move us to repentance and purification, and open us up to that transfiguring communion which is the Kingdom of God.

4. The Problem Focused

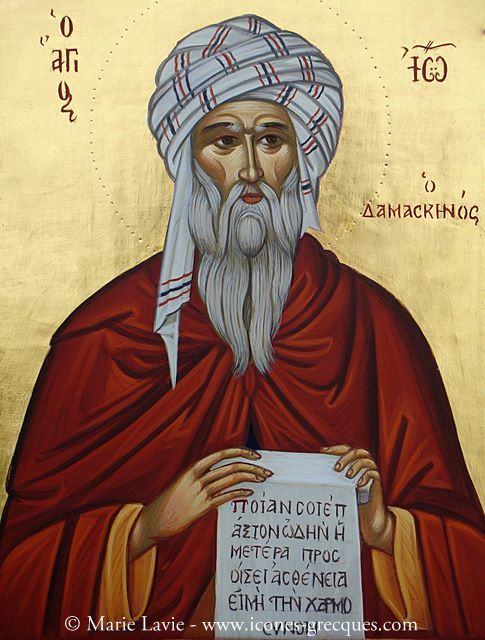

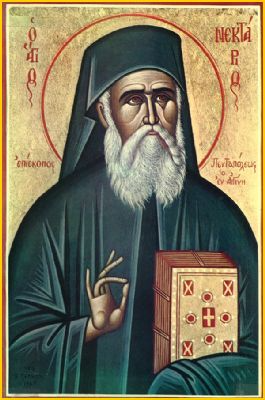

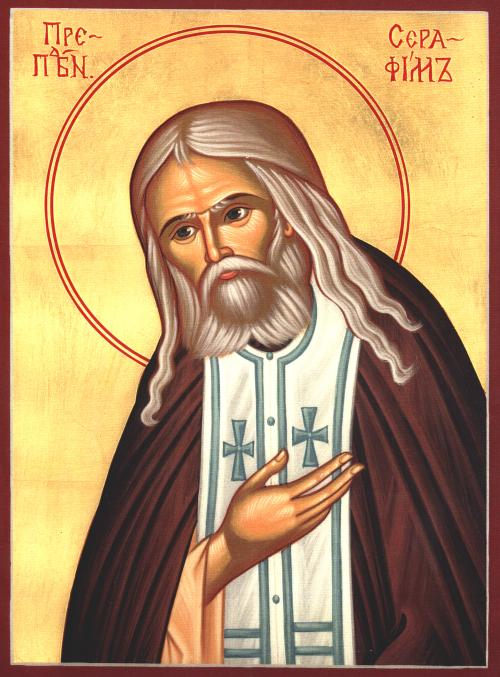

It goes without saying, then, that in those icons whose purpose it is to create immediate personal communion between us (the looked-at-ones) and the saints (the looking-ones), eyes that do not look at us are an obvious obstacle to the achieving of the icon’s basic purpose. (fig. 5) Such icons as the Pantocrator, Hodigitria, individual or grouped saints, ought to look us in the eye, directly and obviously, so as to penetrate us with their transfiguring looks. When, for one reason or another, the saint’s eyes are turned horizontally from a straight on look, when his head is turned 45° from the direct frontal position (fig. 6), or when he is looking up to heaven in a “pious” stare, then communion is lost or greatly diminished. (fig.7)This is evident in certain Hodigitria icons (fig. 8): the Mother of God is “showing us the way” by her hand gesture, but her eyes look elsewhere. Christ blesses us, but does not look at us. The same phenomenon is apparent in certain icons of bishops or priests who, while blessing us, look off to the side. (fig. 9)

It may be said that these “off-in-the-distance” looks of some saints are meant to emphasize their ministry of intercession before God. (figs. 10-12) They look at God on our behalf. It is true, of course, that the saints are our intercessors and that the honor given to the image rises to the prototype, but the purpose of an icon is not to show the saint in intercession but rather to show us the saint in the Kingdom of God and thereby to be a conduit of grace for us. The primary line of vision is “us-ward”: from the person in the Kingdom through the icon to us.

What are the reasons for the saints’ averted looks, for reducing the power of their penetrating glance? Are we to assume lack of talent, sentimentality, lack of knowledge, bad models, etc.? Perhaps the most important thing is simply to draw our attention to the theological and psychological significance of eyes that look directly at us in our iconographic tradition. We thereby strengthen the power of Christ to change people’s lives through the penetrating look of icons.

Fig. 1 St. Nicholas of Myra

Fig. 2 St. Genevieve of Paris

Fig. 3 The Prophet Elijah

Fig. 4 St. Photios the Great

Fig. 5 The Holy Face, Mandilion

Fig. 6 St. John of Damascus

Fig. 7 St. Herodion of the 70 Apostles

Fig. 8 The Mother of God Hodoguitria

Fig. 9 St. Nectarios of Egina

Fig. 10 St. Seraphim of Sarov

Fig. 11 St. Genevieve of Paris

Fig. 12 St. Photios the Great

[1]Archimandrite Spiridon, Mes missions en Sibérie [My Missions in Siberia], Paris, Éditions du Cerf, 1968, p. 84.

[2]Paul Evdokimov, The Art of the Icon: A Theology of Beauty, Pasadena, California, Oakwood Publications, 2011.