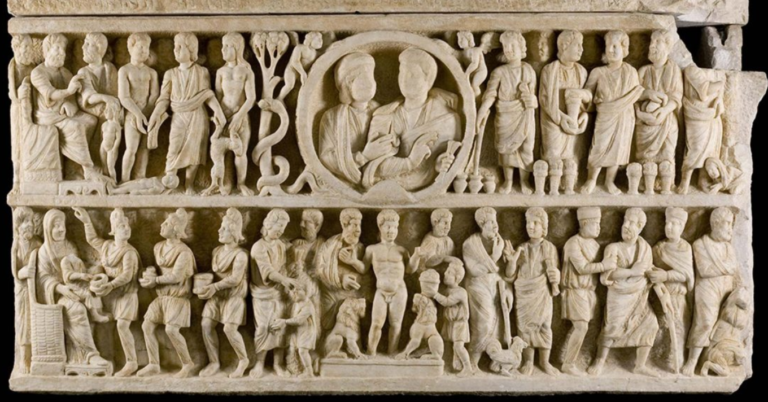

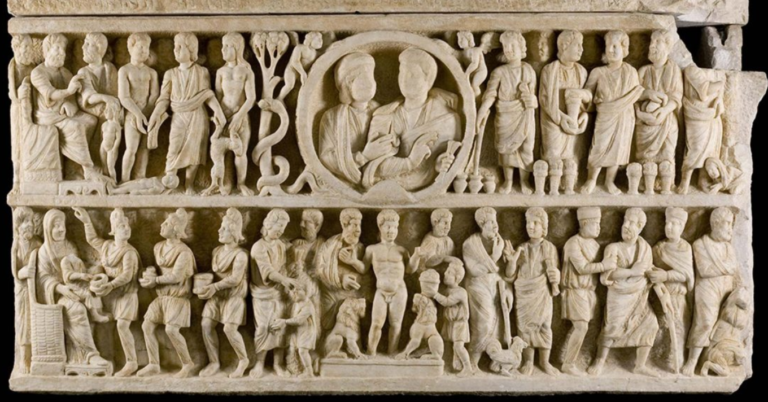

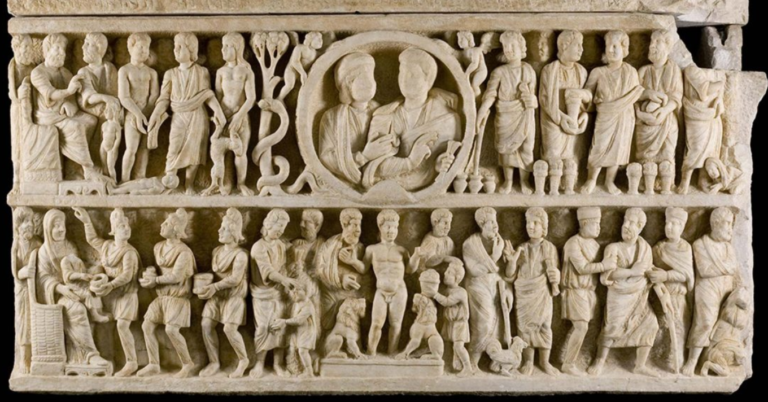

Two Fourth-Century Sarcophagi Misinterpreted Christological, Not Trinitarian

The Thesis The question is whether or not the Catholic worldview—as it relates to anthropomorphic images of God, God the…

The Thesis The question is whether or not the Catholic worldview—as it relates to anthropomorphic images of God, God the…

Father Steven Bigham discusses how Western Christian art developed and has departed from the earlier iconographic tradition.

Des érudits ont interprété certaines images du Sarcophage dogmatique (325-350) à Rome et du Sarcophage de la Trinité-Époux (325-350) à Arles, France, comme les premières images anthropomorphiques de la Trinité. Cette étude vise à infirmer cette interprétation et à affirmer que l'interprétation juste est christologique.

In the Orthodox Church, iconography holds a central and important place, both visually and theologically. Icons are not merely decorations or pictorial teaching aids. They do serve these purposes, but their fundamental reason for being is to bear witness, in an artistic manner, to the Church’s beliefs. They are a reflection of the life in Christ as lived in the Church. We should expect, therefore, to receive from iconography that which is witnessed to and preached by other means, such as Scripture, liturgical texts, dogmatic statements, and the writings of the Fathers.

Many Orthodox Christians reject ecumenism as a panheresy and those who participate in ecumenical activities as disloyal. This attitude, so sweeping as it is, would have to condemn Fr. George Florovsky, hardly, from anyone's perspective, disloyal to Orthodoxy. And yet he participated in many ecumenical activities, was a founder of the World Council of Churches, and felt it absolutely necessary for Orthodox to participate. What is lacking in the contemporary discussion is nuance. This article proposes Fr. George Florovsky as an Orthodox model for ecumenical activity: neither an "ecumaniac" nor a panheretic.

In 1872, the Patriarch of Constantinople in a synod, refused to establish a parallel patriarchate just for Bulgarians on the territory of the Patriarchate of Constantinople. This decision defined and condemned phyletism--parallel Churches on the same territory and organized only for certain ethnic groups.

Cet article raconte mon histoire par rapport à l'œcuménisme : comment j'ai commencé comme un oecuméniste protestant enthousiate pour terminer comme un oeuméniste déçu. Il analyse également ma perception de l'Église orthodoxe dans le mouvement œcuméniquel.

I. Le problème Les chrétiens orthodoxes ont l’habitude de faire bénir les icônes par un prêtre ou un évêque. Souvent…

Allegorical personification played a major role in Graeco-Roman art: a human figure, not a real person, represented an abstract idea. The Christian artistic tradition, culminating in the icon, reduced or eliminated such symbols preferring depictions of real, historical persons and events. This article analyzes specific icons to show how the process developed.

St. Gregory Palamas's doctrine of God's essence and énergies is fundamental for the understanding of icons. God is unknown and unknowable in his essence but manifests himself in his énergies. These énergies shone in Christ Transfiguration, in the Holy Light. It is in this Light that icons depict our world and people in the light of the Heavenly Jerusalem.

Do the changing practices of receiving non Orthodox converts into the Orthodox Church manifest an underlying, but unstated, ecclesiology? These practices have varied, and vary, from baptism to chrismation to simple statement of faith. It is the thesis of this article that the reception of converts presents the Orthodox view about the ecclesiality of non Orthodox Churches.

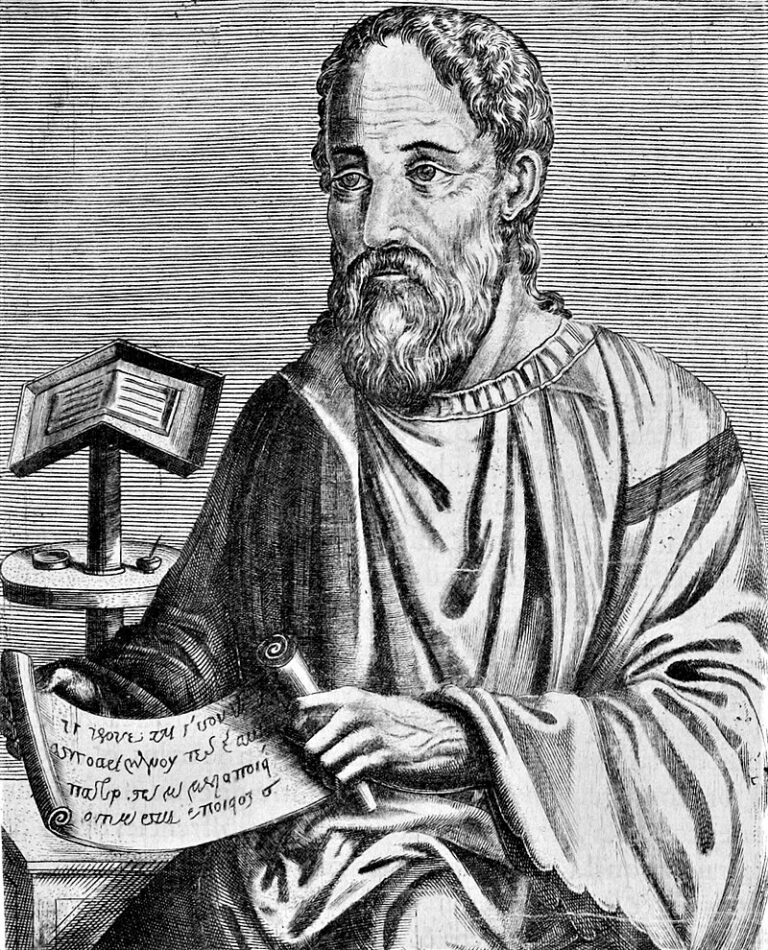

Eusebius of Caesarea is supposedly an iconophobe, but was he really? His Letter to Constantia is the basis of that reputation. This article seeks to prove that that Letter is not authentic and therefore his iconophobic reputation has no basis.