The purpose of this study is to investigate the role of personification within the artistic tradition of the Orthodox Church, that is, in icons. Since we are in the midst of a renaissance of icon painting and study, we assume that most people have a vague idea about what an icon is. The other term in the title of this study, allegorical personification, may be less familiar. By it we mean the following: the visual representation in human form of an idea, quality, or sentiment, such as wealth ; sometimes an image can stand for an object or place, such as a particular city. Personification is a subcategory of allegory in that it restricts itself to human figures, but allegory in a larger sense allows for non-human, figural representation as well, an example being the Russian bear. The essential element in allegory and its subcategory personification is that the artistic forms, human or animal, are not intended to represent actual historical, human persons or real animals. These images are intended rather to point away from themselves to the abstractionswhich it is difficult or impossible to represent directly. It would be an error, therefore, and a confusion of categories, to ask, “Who is that person?” when dealing with an allegorical personification. The proper question to be asked is rather “What does this human form stand for?” Not to be able to distinguish between these two different kinds of human representations, not to know which category of images we are dealing with, is one of the problems of interpreting early Christian art, such as that found in the catacombs.

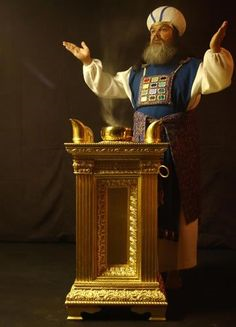

We know that allegory was an important element in the Græco-Roman artistic tradition: examples of such figures as the Three Graces[1](fig.1), the Four Seasons[2](fig. 2), Roman provinces[3](fig. 3) etc. abound. We also know that the orant figure[4] (fig. 4) and the Hermes Kriophoros[5] (fig. 7) have their roots in pagan imagery. The orans also has roots in the Bible (fig. 5),[6] sometimes as personifications of piety and philanthropy respectively. These forms were eventually given a Christian interpretation, but their pagan artistic ancestry goes back to allegorical personification : the Christian orans (fig. 6) and the Good Shepherd (fig. 8).

Græco-Roman art included, of course, images of real historical persons as well as of mythological or heroic persons and gods. This category of representations is shared with the Christian as well as many other traditions.

Christianity entered the Græco-Roman world proclaiming that the God of Israel had intervened in history for the salvation of man. The Lord Jesus spoke and acted in front of witnesses, and the apostles proclaimed a historical Gospel whose truth rested on the fact that they had seen and heard the Holy One of Israel who was crucified under Pontius Pilate. Several New Testament passages contrast Gospel truth and true religion with myths, fables, old wives’ tales, and pointless speculation. (1 Tm 1:4, 4:7, 6:20; 2 Tm 2:15-16 and 4:4-5; Tit 1:14) St. Peter especially contrasts “cleverly invented myths” with “the knowledge of the power and the coming of our Lord Jesus Christ” which he witnessed on the holy mountain of the Transfiguration. (2 Pt 1:16-18) When the apostles speak about Jewish genealogies, gnostic myths, or pointless philosophical speculations, they always contrast them with the historical Gospel of Christ: “the Word became flesh and dwelt among us. . .and we beheld His glory.” This radical, historical orientation of the Gospel, along with a Jewish penchant for concreteness, did not leave much room for allegorical personification of abstract ideas or qualities. Christian preachers, however, soon found themselves in a world that accorded importance to allegorical representations. The stage was thus set for a confrontation, not necessarily violent, between two different ways of representing human persons. At the beginning of Christian imagery, for example in the catacombs, we see both currents mingled together so that it is sometimes difficult to determine whether a feminine orant figure represents a real martyr, the Church, piety, all of these, or something else. Other scenes are obviously historical representations, such as illustrations of Daniel, Lazarus, and Jonah. As Christian art developed throughout the first centuries, we see a marked preference and predominance of the depiction of real people and real historical events as opposed to allegorical personification.

This historical orientation and preference were most clearly expressed in canon 82 of the Council in Trullo (692):

In some pictures of the venerable icons, a lamb is painted to which the Precursor points his finger, which is received as a type of grace, indicating beforehand through the Law, our true Lamb, Christ our God. Embracing therefore the ancient types and shadows as symbols of the truth, and patterns given to the Church, we prefer “grace and truth,” receiving it as the fulfillment of the Law. In order therefore that “that which is perfect” may be delineated to the eyes of all, at least in colored expression, we decree that the figure in human form of the Lamb who taketh away the sin of the world, Christ our God, be hence forth exhibited in images, instead of the ancient lamb, so that all may understand by means of it the depths of the humiliation of the Word of God, and that we may recall to our memory his conversation in the flesh, his passion and salutary death, and his redemption which was wrought for the whole world.[7]

Although the immediate target of the canon is not pagan, allegorical personification but rather Old Testament types of the Messiah, such as a lamb, the Fathers state clearly that they “prefer” the direct image of the real, historical Messiah, Jesus Christ, to indirect images of “types and shadows” which represented the Messiah before His coming. We have a definite devalorization, but not a rejection, of indirect symbols of persons when it is possible to have their direct portrait images. Although the canon deals only with Christ and his Old Testament types, its intent could also apply to Mary and any other saints symbolically prefigured in the Old Testament. Their iconic images are to be preferred to indirect symbols.

But does canon 82 have a bearing on allegorical personification? Not in a direct sense. We can say, however, that the affirmation of images of historical persons as opposed to a certain type of indirect symbolism shows how the Church conceives the relationship of icons to all indirect representations. The pagan, artistic convention of personification is therefore indirectly devalued in the face of representations of historical scenes and persons.

We can see this preference gradually taking over in the first centuries of Christian art. The first attempts by Christians at visual art were probably image-signs, such as the fish or anchor in the case of non-human signs, although we cannot exclude the possibility that Christ and New Testament saints were also drawn. The non-human signs either receded in importance, or were replaced by images with an increasingly historical content. This happened with the orant figure.[8] It was at first a pagan personification of the virtue of piety that had been associated with a deceased person; later it may have represented the Church; then particular saints, eventually the Mother of God, were represented as orants. The pagan kriophoros, a man carrying a sheep on his shoulders, underwent a similar development. At first, it was a pagan symbol for the virtue of philanthropy, but in a Christian context, it became an obvious symbol for Christ the Good Shepherd. This figure may even have been used for direct representations of Christ, as in the mid-fifth century Mausoleum of Galla Placidia, where a kriophoros is shown with a halo and cross, surrounded by sheep (fig. 9).[9] We also notice that during the iconoclastic controversy, the defenders of icons often stated the kinds of icons to be painted, that is, what the content of icons should be. The Council of Constantinople 869-70, in its third canon states this:

If one does not venerate the icon of Christ the Savior, let him not see His face at the Second coming. In the same manner, we venerate and bring homage to the icons of His all-pure Mother, to those of the holy angels painted as they are described in the words of Holy Scripture, and, furthermore, to those of all the saints.[10]

The radically historical orientation of Christianity in general and its iconography in particular, therefore, seem well established.

The question we want to deal with and the problem it raises are the following: Is there a place for the ancient, symbolic form of allegorical personification in the iconography of the Orthodox Church? The thesis that we will try to defend here is that personification is a minor adjunct to the dominant historical orientation of iconography, but at various times and places, the iconographic tradition has deviated from its canonical roots by allowing allegorical personification to have an equal footing with, and sometimes to overshadow, the historical orientation. As a minor element, both in importance and in the amount of space occupied in any particular icon, personification is acceptable, though not necessary. When its size and importance grow beyond their proper place, personification then becomes a threat to the canonical tradition’s theological and artistic balance.

We need to clarify one aspect of the problem: its relation to “symbolism.” The word symbol is very elastic. When we enlarge its definition to include artistic images as well as verbal and mental representations, we enter the vast field of semiology[11], that is, the science of signs and symbols. St. John of Damascus was already aware of at least seven kinds of images, both verbal and visual.[12] The scope of our study is much narrower, however, since we are dealing with a very restricted form of symbolism: a meaning represented by a human form that is not a real person.

We have no objection to real historical persons being portrayed as embodiments of virtues, qualities, sins, or ideas that have been associated with them during their lives. To be likened to Quisling or to Benedict Arnold (for Americans; Canadians see him differently) conveys immediate meaning. Allegorical personification, however, is not this sort of symbolization of a historical person. It is not the adding of a meaning onto a real person but rather the visualization of an abstract meaning in a non-historical human form. Personification is the opposite of symbolic embodiment. Instead of starting with a historical person and moving to an additional meaning, personification starts with an abstraction and moves to its visualization in an empty, human form. Our study deals with this second relation of meaning and human form when it expands its role to rival or overshadow the historical principle.

Let us now look at some of the icons that contain personification in a proper relation to the historical principle.

5.1 The Epiphany Icon

In the icon of the Baptism of Christ, we often see two human figures at Christ’s feet, one a man and the other a woman; sometimes they are riding on the back of fish or sea monsters. The two figures (fig. 10) represent the psalm verse, “The sea looked and fled, Jordan turned back.” (Ps 114:3) The woman is the sea, representing the crossing of the Red Sea by Moses and the children of Israel. As such, she is a prefiguration of baptism. The man has his back to Christ and is an allegory of the Jordan. Elisha turned back the Jordan with Elijah’s mantle forming a dry path through the waters; this is another prefiguration of Christian baptism.

These figures are usually small in comparison to the whole composition and represent important, but secondary, Old Testament prefigurative elements. Were they to be left out or obscured in some way, the Epiphany icon would not suffer in any essential way, and they in fact are not always present in these icons. It is nonetheless interesting to see how each iconographer represents these curious figures as well as the fish and sea monsters that often accompany them.

5.2 The Pentecost Icon

In the icon of the Descent of the Holy Spirit, we have the personification of the world by a crowned man called Cosmos. He represents the world in darkness, on which, through the Church, the fire of the Holy Spirit has descended. It just may be that the personification Cosmos represents a movement opposite to what we saw with the pagan orant and kriophoros figures: instead of personification giving way to real people, we have the representation of real people giving way to personification. In some ancient manuscripts from around the year 1000, several people are represented in the dark space at the bottom of the icon.[13] (fig. 11) These manuscript illuminations may indicate an older and original tradition of representing real, though unnamed, persons present at Pentecost who in turn represent all people. In that case, we would then certainly have an example of reverse development: an allegorical personification replacing real persons.

Whatever the actual historical development of the Pentecost icon may have been, we have an allegory in the figure of Cosmos who occupies the lower, dark space in the composition. Although his size may limit his importance in the composition, Cosmos is by no means an unimportant figure for the icon, and his absence would alter significantly the meaning of the icon. He is necessary to complete the downward movement of the tongues of fire from God, onto the apostles, and through them onto the world sitting in darkness. The Pentecost icon therefore is perhaps the upper limit of the use of personification in the iconographic tradition, and if the manuscript tradition showing multiple uncrowned figures is an indication of an older, iconographic tradition, we may even say that in Cosmos, personification has taken on an exaggerated role. And what if contemporary iconographers replaced Cosmos with several figures?

5.3 The Hospitality of Abraham

Is this icon an example of personification? We do not think so because it is based on the story of the visit of three visitors to Abraham and Sarah; the biblical and ecclesiastical tradition considers the story to be historical, involving real people. Whether the mysterious visitors in the icon are interpreted as a Trinitarian epiphany or as an appearance of the Word and two angels or men, we are still dealing with a historical event onto which a Trinitarian or christological interpretation has been added. Both interpretations are in fact present in the tradition, though the christological one is the older one. The biblical account itself is inconsistent in that it gives different identities to them.[14] (Gn 18-19)

The most famous rendering of this icon is, of course, that of Rublev, who reduced the historical elements to a minimum and even eliminated Abraham and Sarah completely. The reduction of the historical elements naturally increases the non-temporal and non-spatial feeling surrounding the angels, but they are in fact images of actual visitors, of whatever nature, whom the tradition has interpreted in various ways. This icon is therefore not an example of an allegorical personification but rather the interpretation of a historical event. If the image is interpreted in a christological way, it is simply a visualization of a historical event. On the other hand, a Trinitarian interpretation imposes a “symbolic” meaning on top of a historical event. Since the Church’s iconology cannot accept an actual image of the Father and the Holy Spirit, the two other visitors are seen as real angels who “symbolically” or allegorically represent the Father and the Holy Spirit while the middle figure is the Logos. The biblical text creates another problem for the Trinitarian interpretation since it says that two of the visitors went to Sodome while “Yahvé” or “the Lord” stayed behind and talked with Abraham. If we take the Trinitarian interpretation, already somewhat convoluted, there is the problem of “dividing” the Trinity when the Logos remains behind to speak to Abraham and the symbols of the Father and the Holy Spirit go off to Sodom. In many ways, the christological interpretation is preferable.

5.4 An Image of the Adoration of the Magi

In the Dokhiariou monastery, there is a 17th—century fresco that resembles the Adoration of the Magi.[15]It is in fact an illustration of one of the stichera sung at Christmas vespers:

What shall we present unto Thee, O Christ,

For Thy coming to earth for us men?

Each of Thy creatures brings Thee a thank-offering:

The angels—singing; the heavens—a star;

The Wise Men—treasures; the shepherds devotion;

The earth—a cave; the desert—a manger;

But we offer Thee the Virgin-Mother. O Eternal God, have mercy upon us.

The Mother of God, holding the Christ Child, is placed in the middle of the image surrounded by the various elements mentioned in the sticheron. The iconographer wanted to represent each of the gifts mentioned in the text and obviously took the Christmas icon as his model. A star shines in the sky; the angels sing; the shepherds show their amazement; the Magi offer their gifts. But to represent the earth and the desert, the artist painted two women who personify these natural elements. The woman representing the earth carries a cave, and the woman representing the desert, who looks like St. Mary of Egypt, holds a manger.

First of all, we must note that this image does not represent an event, in the strictest sense, even though elements of the Christmas icon are incorporated in it. It is rather an illustration of a liturgical text. We see that the artist has already given in to the current of his time by moving away from a strict historicity. He has given a visual form to a poetic text, and to accomplish his objective, he has combined historical elements with allegorical personification. In itself, this image does not give an exaggerated place to personification, but we know that the inspiration behind the work, that is, the desire to illustrate a text, gives artists a much greater chance to exercise their imagination, even their fantasy. This is precisely what the Church has always fought. This tendency went hand in hand with the degradation of the canonical tradition itself, and, in our opinion, this was no accident. When we see images of the Mother of God and Child seated on/in a fountain (fig. 12), an image meant to illustrate the poetic image of “The Mother of God, the Fountain of All Joy,” we need to ask ourselves if there is not perhaps a better way to illustrate the idea. Why not behind the fountain?

5.6 Icons of Saints

Because of the wide variety of icons of the saints, it is difficult to make a survey of all such icons and to determine the place of personification in them. The very fact that images of saints are of historical persons, however, tips the balance away from an important role for this kind of symbolism. It is not to be excluded, but our guess is that it is rather rare.

We might mention, nonetheless, the four symbols for the evangelists, one of which is a winged, human figure standing for St. Matthew. Is this really an image of an angel coming, from Ezekiel’s vision (Ez 1:14-25) and reflected in Rv 4:6-8, or some other heavenly creature? Whatever may be the history and interpretation of these symbols, it is certain that the winged man is not a direct image or icon of St. Matthew. It is rather a human form symbolizing the evangelist or his gospel. Used in this context, it is a personification, but due to its Old and New Testament roots as well as its relatively infrequent usage, we cannot consider it to be an abuse of the historical principle.

Are icons of Saint Sophia and her three daughters, Faith, Hope, and Charity, meant to represent real women saints? Even if they are so intended, has Christian history simply assumed that real people stand behind what were originally allegorical personifications of Christian virtues? If this is the case, we have a very good example of how the Church feels somewhat uncomfortable with “hollow” representations of the human form. Even where there were no real saints behind the images, the Church “created” four new ones to fill the void.

We have seen that the phenomenon of allegorical personification has a very minor place in the canonical tradition of iconography. There are, however, examples of what we would call real distortions in which personification takes on an exaggerated role and thus deforms the canonical tradition.

6.1 Psalter Illustrations

Throughout the history of Christian art, there have been revivals of classical elements. Manuscript illumination is one of the art forms that has shown itself rather susceptible to the ebb and flow of these revivals. Because these images are not intended for liturgical use in the churches, though they are closely related to the icons painted in the churches, we see a greater degree of latitude and thus a lessening of the canonical requirements. A good example of the greater latitude found in illuminations is seen in the fact that the iconoclastic struggle is reflected visually in Psalter illuminations just after the iconoclastic controversy of 725-843, but it is never shown in the iconography of the churches.[16]

We have an illuminated, Byzantine Psalter from the 11th century (Bibliotheque nationale, Paris) in which there is an image of King David in the company of two female figures personifying wisdom and prophecy; they inspire David, who holds a Psalter.[17] (fig. 13) Since there are two, rather large figures, the personification principle is at least as important as the representation of the historical David.

6.2 God the Father

We have a strange and aberrant use of personification in direct depictions of the Trinity, and God the Father. We are not speaking here of the Hospitality of Abraham which is an indirect image of the Trinity, if we accept the Trinitarian interpretation. Images of an old man representing God the Father are justified as making visible, certain traits expressing the idea of the first Person’s fatherhood. (fig. 14) Realizing that the natural tendency of Orthodox Christians on seeing a human form in an icon is to ask “Who is that?,” thus assuming that a real person stands behind the image, and realizing as well that an image of the Person of the Father is impossible and impious, Bogoslovsky says that the image of an old man in relation to God the Father is a scriptural visualization of the anthropomorphisms concerning God. These images are therefore personifications of the idea of fatherhood and are not intended to be images of God the Father himself. [18]18

Not only do we have here a major clash with the ecclesial tradition which condemns any attempt to visualize or paint the Father directly, but we also have a major clash of the personification principle with the iconographic principle which sees a human form in an icon as being the representation of the real person. In this image, we see a human form which has no real person, hypostasis, behind it; the Father’s image can stand behind no created image, yet it is claimed that somehow this image represents the Father. The result is that personification is raised to the same level as the iconographic principle in a very important area, the doctrine of God, and causes a serious imbalance resulting in iconographic heresy. An allegorical personification of the idea of fatherhood is set beside the image of Christ to which is added an indirect, symbolic representation of the Holy Spirit. This representation is taken out of its natural setting, that of the Baptism of Christ. Of all the other historical and theological objections that can be made against these images of the Trinity, the one based on the improper and exaggerated use of personification is not the least among them.

We have a second use of personification to justify images of God the Father in the sophiology of Fr. Sergius Bulgakov, a Russian emigré priest who taught at St. Sergius Orthodox Institute in Paris just after the Revolution. His sophiology assumes that there is an eternal and divine humanity in God, which he calls the divine Wisdom (Sophia), and that the image of an old man is an image of God’s eternal and divine humanity.[19] Bulgakov rejects the apophatism of the Fathers, and consequently the iconology worked out at the time of the iconoclastic controversy. Such a theology believes in a God Who, essentially invisible, becomes visible in the Incarnation. Bulgakov rather claims that God is visible and representable in “his divine and eternal humanity” (divine Wisdom), which has been drawn and projected in created humanity. Leaving aside the highly questionable nature of his sophiology, the Church’s iconology, as opposed to Fr. Bulgakov’s, says that icons represent real persons in the visible aspects of their natures. Unless we want to say that the divine Wisdom is a Fourth Person of the Trinity, and Fr. Bulgakov always denied that this was his doctrine, the image of an old man representing “the eternal and divine humanity of God” can only be a personification of a non-person, a thing or idea. Whatever we want to make of Fr. Bulgakov’s complicated argumentation as well as of his surprising notion of an “eternal and divine humanity—the Divine Sophia—in God,” his ideas do not make the image of an old man in a direct depiction of the Trinity anymore acceptable.

6.3 The Divine Sophia

In his book on iconography, Paul Evdokimov[20] explains and defends the image of the Divine Wisdom. In a late 16th-century Novgorod icon reproduced in his book, (fig. 15), we see the Divine Wisdom portrayed as a crowned, angelic figure seated on a throne, with the Mother of God and John the Baptist on either side. Above the central figure, is Christ with a throne directly above His head and angels on either side of the throne. Evdokimov follows in the sophiological tradition of Fr. Bulgakov and sees in this enthroned angel an image of the Divine Wisdom: “And finally, the angel in the middle is Wisdom as the personified Source of energies and sanctification, pneuma-Spirit without the article.”[21] The other figures in the image represent the different ways in which wisdom has been explained. We are not concerned with them because they are, in fact, examples of what is a normal, iconographic principle: real persons, human or angelic, are given a symbolic meaning. Christ is Christ; Mary is Mary; John the Baptist is himself; and the angels represent real angels. But then comes the fundamental iconographic question: “Who is that in the middle?” The answer is, of course, that it is a “non-person,” but as Evdokimov says himself it is “the personified Source of energies and sanctification.” The personified source of something is not a “someone” and therefore runs up against the ecclesial tradition which requires that a human form, occupying so central and dominant a position in an icon, represent someone, not something.

The first problem that we see with Evdokimov’s explanation is not so much that a personification is at the center of an image, though that is a problem. The real difficulty is found in sophiological theology and its intricate and at times mystifying argumentation. Having designated the Divine Wisdom as a quasi-substantial though non-personal element in God himself, what other means but personification can the proponents of sophiology use to make an image of what they consider to be such an important principle? The personification of divine Wisdom seems abhorrent because it shows that some Orthodox are not satisfied with painting Christ the Wisdom of God in His historical image. As a result, a symbolic image pushes the historical image out of the center and thus violates canon 82 of the Council of Trullo. Sophiological theology seems to exceed the bounds of the larger ecclesial tradition by identifying something that is “divine and eternal” in God which is neither persons, nature, nor energies. The application of sophiological theology to iconography only compounds the excess.

The image of Divine Wisdom is, however, a very pointed example of the close relationship that exists between a theological vision and iconography. A contaminated, theological vision will eventually manifest itself in contaminated iconography. Being a theological art form, iconography can and must be evaluated not only from an artistic perspective but also from a theological one. Personification as an artistic element, which if subordinated and overshadowed by the historical principle of iconography, can have a place, but when theologians and artists overstep the boundary established by the ecclesial tradition, personification then becomes a vehicle which corrupts the art of the Church and makes visible a heterodox, theological vision.

Fig. 1 The Three Graces

Fig. 2 The Four Seasons

Fig. 3 The Roman Province of Italia

Fig. 4 The Poppy Goddess of Crete

Fig. 5 The Jewish High Priest Offering Incense

Fig. 6 A Christian Orans in the Roman Catacombs

Fig. 7 Hermes Kriophoros

Fig. 8 A Christian Good Shepherd from the Roman Catacombs

Fig. 9 Christ the Good Shepherd

Fig. 10 Icon of the Epiphany; the Figures at Christ’s Feet

Fig. 11 An Armenian Image of Pentecost; Many figures in the Lower Half-Circle.

Fig. 12 The Mother of God, the Fountain of All Joy

Fig. 13 11th Century Byzantine Psalter showing King David with Wisdom and Prophecy

Fig. 14 A Direct Depiction of the Trinity: God the Father Personified as an Old Man

Fig. 15 Divine Wisdom (Sophia), Novgorod

[1] Michael Grant, The Art and Life of Pompeii and Herculaneum, New Week Books, NY, 1979. p. 57.

[2] http://www.romanoimpero.com/2013/07/sabratha-libia.html

[3] Brass sestertius of Trajan, Rome mint, 103-111 CE smaller version. Similar to the coin above celebrating Trajan’s alimenta. On the right, Trajan, wearing a toga and holding a scepter, sits on the sella curulis and extends his right hand toward a woman standing before him holding an infant in her left arm and resting her right hand on a slightly older child standing at her feet; both children extend their hands toward the emperor. The female has been identified as the personification of Italia. The inscription reads S[enatus] P[opulus]Q[ue] R[omanus] OPTIMO PRINCIPI S[enatus] C[onsulto] ALIM[enta] ITAL[iae]. Berlin, Bode Museum. Credits: Barbara McManus, 2012.

[4] https://www.google.ca/search?q=the+poppy+goddess+of+cr%C3%AAte&tbm=isch&tbo=u&source=univ&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwimvduCoYrYAhXF4IMKHeJfAd4QsAQILg&biw=1024&bih=621#imgrc=mwp_iYSY8NqRwM:&spf=1513280463098

[5] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kriophoros

[6] https://i.pinimg.com/736x/ba/e0/e7/bae0e7415a54f35696db280e2fe20f2c–lds-temples-holy-land.jpg

[7] The Seven Ecumenical Councils, The Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, Eerdmans, 1979, p. 401.

[8] André Grabar, Christian Iconography :A Study of Its Origins, Princteon, pp. 74 ff.

[9] Nunemoto Yanagi et al., Byzantium, Chartwell, Secaucus, NJ, 1978, pp. 15-17. http://www.ravennamosaici.it/musei/galla-placidia/?lang=en

[10] Leonid Ouspensky, Theology of the Icon II, Anthony Gythiel, tr., St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, Crestwood, NY, 1992, p. 212.

[11] Charles Bernard, “L’activité symbolique,” Théologie symbolique, Téqui, Paris, 1978, pp. 9-124; Egon Sendler, “Theories of the Image,” The Icon :Image of the Invisible, Oakwood, Redondo Beach, CA, 1988, pp. 74-78.

[12] St. John of Damascus, On the Divine Images, David Anderson, tr., St. Vladimir’s, Crestwood, NY, 1989, pp. 74-78.

[13] See the reproductions of Pentecost icons in George Galavaris, The Illustrations of the Liturgical Homilies of Gregory Nazianzinus, Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, 1969; Léonide Ouspensky, “Quelques considérations au sujet de l’iconogrpahie de la Pentecôte” [Some Considerations on the Subject of the Iconography of Pentecost], Messager de l’Exarchat du patriarcat russe 33-34, Paris, 1960; Christopher Watler, “La Pentecôte,” L’iconographie des conciles dans la tradition byzantine, Paris, Archives de l’Orient Chrétien 13, 1970, pp. 190-214.

[14] L. Thunberg, “Early Christian Interpretations of the Three Angels in Gen. 18,” Studia Patristica, VI, Texte und Untersuchungen, 92, Berlin, 1966, p. 13.

[15] Philip Sherrard, Athos the Holy Mountain, Overlook Press, Woodstock, NY, 1982, p. 13.

[16] Theology of the Icon, pp. 218-220; see the Chudov Psalter, State Historical Museum, Moscow, p. 150 and p. 152 in Robin Cormack, “Painting after Iconoclasm,” Iconoclasm :9th Spring Symposium on Byzantine Studies, Birmingham Centre for Byzantine Studies, University of Birmingham, UK, 1977, pp. 142-163; André Grabar, L’iconoclasme byzantin, Paris, Flammarion, 1984, pp. 369-376.

[17] This image is used as the cover for a French translation of the psalms from the Greek Septuagint : Les psaumes :prières de l’Église, Père Placide Deseille, tr., YMCA-Press, Paris, 1979.

[18] See the discussion of Bogoslovsky’s justification, Theology of the Icon, pp. 385-387.

[19] See the section on Bulgakov’s doctrine in Theology of the Icon, pp. 387-391;

[20] Paul Evdokimov, “The Icon of the Divine Wisdom,” The Art of the Icon :A Theology of Beauty, Oakwood, Redondo Beach, CA, 1990; John Meyendorff, “L’iconographie de la Sagesse divine dans la tradition byzantine” [The Iconography of the Divine Wisdom in the Byzantine Tradition], Byzantine Hesychasm :Historical, Theological and Social Problems, Variorum Reprints, London, 1974, pp. 259-277.

[21] Ibid., p. 350.