1. INTRODUCTION

In this chapter, we would like to continue the analytical work begun in another work[1]1 where we examined the writings and archaeology of Jews and Christians during the first three centuries of Christian history to determine their attitudes toward non-idolatrous images. We chose the year 313 as the terminus ad quem because it was at that date that Constantine assumed authority in the Western Roman Empire, thus, inaugurating what history has come to call the Christian Empire.

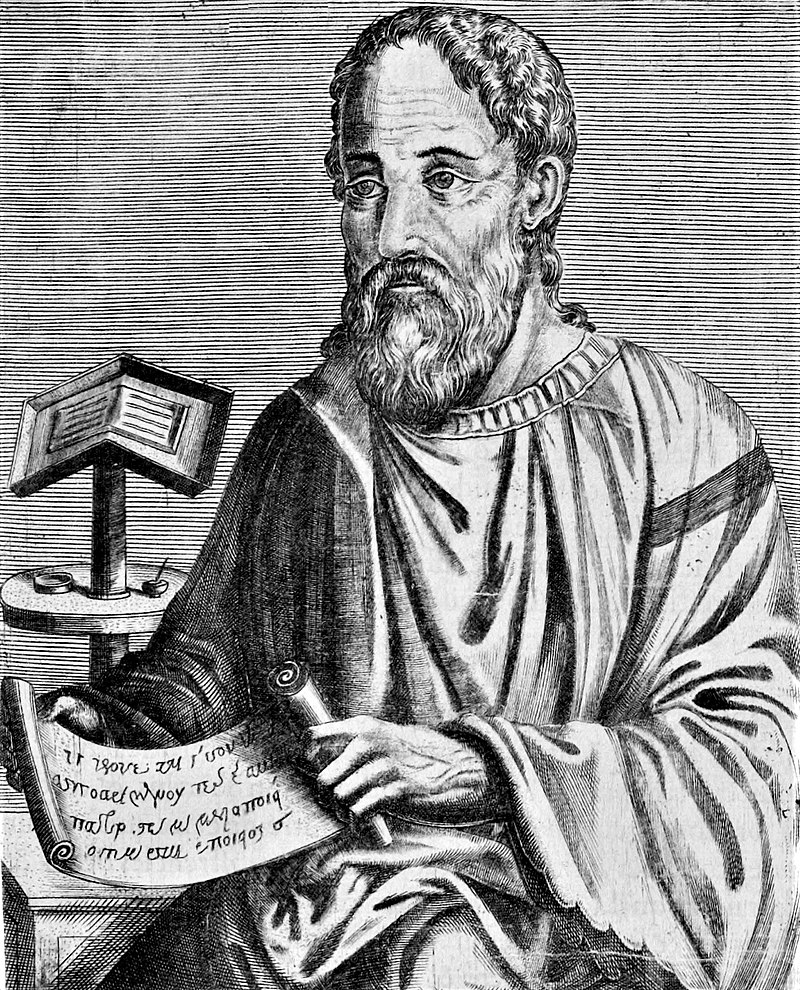

Eusebius of Caesarea (270–340) is certainly an important figure at this turning point in the history of the world and the Church. His literary work, to say nothing of his historical role in the theological controversies of the time, is considerable. Everyone is agreed in applauding his contribution to Church historiography. There are, on the other hand, divergent opinions about his theology and his place in the Church. Since Eusebius favored Arius and opposed the Council of Nicaea in 325, as well as Athanasius of Alexandria, his name has been tainted with heresy. Many consider Eusebius to have been an iconophobe as well as an Arian. Although the historicity of this characterization, iconophobe, is considered to be well founded, we would like to examine this dominant opinion to see if it is in fact grounded in the historical evidence.

The witness of Eusebius is all the more important because it furnishes us with precious information about Christian, and other, images that existed at his time. Due to this data, and especially due to the various interpretations that have been made of it, Eusebius has an undeniably important place in the endless disputes about early Christian art. We propose studying his writings to see what they tell us about the place of figurative art in the Church at the end of the 3rd and the beginning of the 4th century. In the light of this data, we will be better able to determine what Eusebius thought of Christian art. By studying his writings, we want to answer two general questions: 1) What data does Eusebius provide about existing Christian images in his time? and 2) What was his attitude toward them?

Let us look, first of all, at the chronology of Eusebius’s works in which he refers to images. What follows is only relative since specialists in the field cannot themselves agree on a definite chronology. We have, therefore, accepted the dating established by Wallace-Hadrill[2]2:

| 1. | before 303 | The History of the Church, chapters I—VII |

| 2. | after 309 | Commentary on Luke |

| 3. | before 313 | The Proof of the Gospel |

| 4. | after 318 | The History of the Church, chapters I—IX |

| 5. | 313-324 | Letter to Constantia |

| 6. | 337 | The Life of Constantine |

2. AT PANEAS, THE STATUE OF CHRIST AND THE WOMAN WITH A HEMORRHAGE: THE HISTORY OF THE CHURCH VII, XVIII.[3]3

A. What images does this text highlight?

In this first text (see the annex), Eusebius informs us of the existence of two sorts of Christian images: 1) at Paneas, a bronze work composed of two statues, one said to be of Christ and the other of the woman with a hemorrhage; 2) colored portraits of the Apostles Peter and Paul, and Christ. The local tradition at Paneas claimed that the statue reproduced the real features of Christ, but Eusebius does not seem to be convinced: “This statue, which was said to resemble the features of Jesus.” For the portraits, however, he gives the impression of believing in the truth of the claim: “It is not at all surprising that Gentiles should have expressed their gratitude thus, for the features of His Apostles Paul and Peter, and indeed of Christ Himself, have been preserved in colored portraits which I have examined.” It is significant that Eusebius does not exclude the possibility of real portraits of Christ and the Apostles. Does not such a belief suppose, at least in Eusebius’s mind, a series of portraits that go very far back in history, if not to apostolic times? How could there be a realistic portrait of a person, some 250 years later, without a model having been made while that person was alive? Of course, Eusebius’s opinion, in itself, proves nothing about the historicity of a chain of portraits representing Christ and the Apostles. Such an opinion, however, would show that Eusebius did not think that possibility absurd, impossible or impious.

B. What is Eusebius’s attitude toward the images?

Eusebius manifests a favorable attitude toward these images: he notes the following about this little chapter: “I do not think I ought to omit a story that deserves to be remembered by those who will follow us.” In addition, he says that the statues were “a wonderful memorial of the benefit the Savior conferred upon her” and “it is not at all surprising that Gentiles . . . should have expressed their gratitude thus.” Even if the woman with a hemorrhage in the Gospel story did not really set up the statues, it does not seem inconceivable to Eusebius that she could have done such a thing. Does Eusebius seem to be scandalized by the very existence of the statues or by the fact that some claim that the woman with a hemorrhage set them up? Apparently not. Does he attack them as a violation of the 2nd Commandment? No. The tone of the whole chapter shows rather his admiration of the woman’s thank-offering. As for the portraits, he does not show any antipathy toward them. This is all the more significant because, as we will see later with regards to the portraits of Christ and Paul, Eusebius manifests a strong hostility toward such images—if, indeed, the letter is authentic as we have it. Since this first text is part of Eusebius’s unquestionably authentic writings, we must give it great weight in evaluating his attitude toward Christian images.

In his On the Divine Images,[4]4 St. John of Damascus refers to this Eusebian text as a statement in favor of Christian images. He certainly would not have quoted such a text if he had detected in it the slightest antagonism toward images. The 8th-century iconoclasts themselves did not understand the story of the statues as a hostile expression toward Christian images. Had they detected the slightest antagonism, they would certainly have cited it as a confirmation of Eusebius’s, and the early Church’s, supposed iconophobia. For St. John, Eusebius was an iconodule, or at least not opposed to Christian images, despite his reputation for other doctrinal deviations.

Certain modern scholars[5]5 believe they have detected a negative attitude on Eusebius’s part when he speaks about the pagan custom of honoring benefactors by erecting commemorative statues. They understand the description of the woman’s gesture, a “Gentile custom,” as a condemnation of her action. Such a pejorative interpretation is certainly in conflict with the beginning of the passage where Eusebius says that the “story deserves to be remembered by those who will follow us.” If there is any ambiguity in the last sentence of the chapter, it must be interpreted in the light of the opening sentence in which the meaning is clear. What seems normal, that is, “not at all surprising,” to Eusebius is not the continuation of an abominable and idolatrous custom in the Church, but rather that the former pagans would have purified one of their customs of idolatry and used it to honor the Savior.

On the basis of this text alone, it is difficult to claim that Eusebius of Caesarea was iconophobic, and since The History of the Church is the first of his works, around 303, to speak of Christian images, it is rather a witness to his iconodulia—at least neutrality—instead of to his iconophobia.

If, in fact, the monument at Paneas was an image of the healer god, Asclepius, and an unknown suppliant[6]6, we have a good example of a well-known process: Christians emptied a pagan, artistic form of its content and filled it with a Christian meaning. They adopted and adapted elements of pagan imagery to their own needs. If Eusebius himself was aware of the Christianization of a pagan monument, or even if he suspected, he says nothing concrete to indicate this awareness. The only thing he says in this regard is that the statue “was said” to resemble Christ.

3. AT PANEAS, THE STATUE OF CHRIST AND THE WOMAN WITH A HEMORRHAGE: COMMENTARY ON LUKE 8: 43–48.[7]7

As we can see, this text is nearly identical to the preceding one in what it says about the woman with a hemorrhage. The Commentary differs from the History in that there is a problem of authenticity surrounding the former writing. It is, in fact, unlikely that the Commentary, as we have it, comes from Eusebius. The third-from-the-last line, at least, is certainly not Eusebian: according to the historian Sozomen,[8]8 Emperor Julian (361–363) destroyed the bronze monument. According to the Commentary, Maximin Daia (308–313) destroyed it. Such gross historical error cannot be attributed to Eusebius. Whatever we want to say about the authenticity of the Commentary, our argument is unaffected since the Commentary brings to the fore no new information. If Eusebius is not the author of the Commentary, his History of the Church is quite sufficient to support our thesis. If he is the author, we simply have a restatement of the testimony already established.

4. THE IMAGE OF THE THREE VISITORS TO ABRAHAM: THE PROOF OF THE GOSPEL V,9[9]9

A. What images does the text highlight?

We learn from this passage about the existence of an image at the place, the Oak of Mamre, where Abraham received three mysterious visitors. (The Orthodox iconographic tradition calls this image the Hospitality of Abraham.) In this image, the three visitors “sit one on each side, and he in the midst surpasses them in honor.” The content of the image, the subject, is both historical and symbolic: historical because the biblical text, as well as its traditional interpretation, sees in it the story of a real, historical event. As such, the image is the illustration of a biblical story, but it is also symbolic because, for Eusebius, one of the visitors is/represents Christ. In the tradition of the Church, the event and the image of the Hospitality of Abraham also have a symbolic interpretation, both Christological and Trinitarian. The more ancient tradition sees in the event a prefiguration of Christ, accompanied by two angels; the other tradition, later, sees three angels symbolically representing the Trinity. The two interpretations, however, do not necessarily exclude each other.[10]10 Eusebius says nothing about the age of the image and expresses no opinion on the matter.

B. What was Eusebius’s attitude toward the images?

In this passage of The Proof, Eusebius gives his interpretation of Gn 18:19–25 according to which the words that Abraham addresses to one of the three visitors can only be spoken to the Lord himself, Christ, in a human form that prefigures the Incarnation. Eusebius refers to the image in passing, simply as a visual illustration of his exegesis. He shows a positive attitude toward the image or, at least, does not say anything negative. There is not the slightest hint of hostility toward images in general or toward this one in particular. What is more, St. John of Damascus included this passage among the patristic texts in favor of iconodulia, the second Eusebian text cited by St. John in favor of Christian images. St. John’s opinion of Eusebius on this question is quite clear. The authenticity of the text is not a problem here.

5. THE CROSS IN THE HAND OF A STATUE OF CONSTANTINE: THE HISTORY OF THE CHURCH IX, IX, 10[11]11

A. What images does this text highlight?

In this passage, Eusebius deals with a cross and a statue of the Emperor Constantine, both three-dimensional. We obviously do not need this passage to establish the existence of imperial statues, but the association of the emperor’s statue with the image of the cross, as a symbol of victory, is quite new. At the time, it was no doubt very striking, for Christians and for pagans, to see a cross intimately associated with the emperor’s image. We do not know to what degree Christians were accustomed before this event to seeing a cross in public, but the gesture of Constantine certainly gave a new visibility and legitimacy to this image of torture transformed into a symbol of military and political victory.

B. What was Eusebius’s attitude toward the images?

Eusebius’s attitude toward the statues of pagan Roman emperors is not pertinent to our study. These statues were considered to be idols, and it is not difficult to imagine his attitude. It is important to determine, however, his attitude toward the statue of a “Christian” emperor. What should one do with a “de-idolized” statue of a “de-deified” emperor? Our text says nothing on the matter. Eusebius, however, tells the story as though it is a manifestation of Constantine’s Christian piety. For him, the two images associated together, eloquently but silently, proclaim the victory of the Christian empire over the pagan empire. If Eusebius felt ill at ease in front of a publicly exposed cross, in front of the new type of imperial statue—unchanged in appearance but revolutionary in meaning—or in front of the two put together in one monument, his text gives no hint of his feeling. And finally, St. John quotes this chapter, the third Eusebian text, as another piece of evidence supporting the Christian iconographic tradition. The authenticity of the writing is not in question.

The emperor’s statue furnishes us with an example of the flexibility of the Christian attitude toward two types of images. According to Pliny the Younger and other authors, Christians refused to sacrifice to the statue of the emperor.[12]12 Since the Roman civil religion raised the emperor to the rank of a god, his statue was an idol. Eusebius no doubt shared this point of view, but when the emperor refused divine honors and declared himself human, his statue lost its idolatrous quality. For Eusebius, and for all Christians, a cross in the hand of a statue of Diocletian, for example, would probably have been shocking and impious, but a cross in the hand of a statue of Constantine, the 13th Apostle, was a symbol of victory and glory. Eusebius’s attitude, and that of Christians in general, toward an image depended on the nature of that image, whether it was idolatrous or not.

Up to this point in our study, based on authentic texts, Eusebius has not shown the slightest iconophobia. The fact that he noted the existence of a non-idolatrous image is proof in itself of his approval of an art purified of idolatry. The fact that St. John of Damascus cited Eusebius three times shows that he considered the bishop of Caesarea to be in the iconodule camp.

6. A CROSS IN THE HAND OF A STATUE OF CONSTANTINE AND ITS INSCRIPTION: THE LIFE OF CONSTANTINE I, XL.12[13]13

Since we are dealing for the first time with The Life of Constantine, we need to touch on the problem of this document’s authenticity. Controversy has been raging for a long time,[14]14 and the question of the Life’s authenticity is obviously capital since we want to use it as evidence for Eusebius’s attitude toward images. Unfortunately, there is no consensus on the question. At the same time, one common position seems to be emerging: Eusebius is the author of the core of a document composed right after Constantine’s death in 337. Subsequent authors probably added other sections and rewrote some parts. After a review of representative authors on the question of the Life’s authenticity, we note that the sections that refer to images are not among the contested passages. At the beginning of the Life, Eusebius states his intention: “the design of my present undertaking being to speak and write of those circumstances only which have reference to his religious character.”[15]15 The parts that interest us specifically deal with Constantine’s piety and, therefore, are part of the Eusebian core. If, on the other hand, future scholars prove the opposite, the conclusions of this study will not be affected because the same passage is contained in The History.

The Life of Constantine, written in or after 337, claims to set out historical events that took place between 313 and 337: the first being the date when Constantine came to power in the West and, the second, the date of his death. The Eusebian core expresses Eusebius’s attitude at the end of his life, in 340. We, therefore, feel it is possible to search the Eusebian core for historical data concerning images that existed at the beginning of the 4th century as well as for evidence of Eusebius’s attitude toward non-idolatrous, figurative art.

Since this passage of The Life provides essentially the same information contained in The History, the reader can refer to the comments we made on this material. See 4 above.

7. REJECTION OF CHRIST’S IMAGE:“THE LETTER TO CONSTANTIA”[16]16 Eusebius’s iconophobic reputation is based solely on a letter he supposedly wrote to Constantia, Constantine’s half-sister, in answer to her request that Eusebius send her an image of Christ. Eusebius refused and castigated the empress for having dared to ask for such a thing. No other Eusebian writing or gesture is cited to support his supposed iconophobia. His anti-image reputation depends entirely on the authenticity of this letter. If Eusebius did not write the Letter at the beginning of the 4th century and if it is rather a fabrication of 8th-century iconoclasts, the idea of Eusebius’s hostility toward Christian images has no foundation whatsoever. If Eusebius’s iconophobia falls with the letter’s authenticity, a major element of a widely spread “rumor” also falls: the claim that the Christians of the first three centuries were hostile toward non-idolatrous images.

This Letter is unknown before the iconoclastic council of Hieria in 754; it was first quoted in that council. The letter thus makes its entry onto the historical stage some 400 years after its presumed composition.[17]17 The Seventh Ecumenical Council in 787 refuted the decree of Hieria and reproduced two sections of the letter. Since the 8th century, everyone, iconophobes and iconodules, has put the bishop of Caesarea in the camp of those who have been hostile to Christian images. We have already noted, however, the opposite opinion of St. John of Damascus about Eusebius. As a result, iconophobes after the 8th century have considered Eusebius to be an ally. The following is a reconstitution of the letter’s historical transmission[18]18:

313–325 Eusebius supposedly wrote the letter.

325 – 754 The letter was supposedly transmitted in collections of Eusebius’s writings without, however, creating an echo in any other writing.

754 The iconoclastic council of Hieria quoted the letter in defense of its position against icons.

787 Nicæa ll quoted two sections of the letter in its refutation of Hieria.

818–820 Patriarch Nicephorus I of Constantinople quoted other fragments in his Contra Eusebium et Epiphanidem and Refutatio et Eversio.

1702 F. Boivin assembled the sections in a note added to an edition of Byzantina Historia of Nicephorus Gregoras, a Greek scholar of the 14th century.

1830 L. Schopen reproduced Boivin’s text in a new edition of Byzantina Historia.

1852 J. Pitra reproduced the letter in Spicilegium Solesmense 1.

1860 J. Migne published Boivin’s compilation.

1968 H. Geischer included the letter in Der byzantinische Bilderstreit.

1969 H. Hennephof reproduced the letter in Textus byzantinos ad iconomachiam pertinentes.

1972 Cyril Mango published an English translation.

The authenticity of the letter is the problem. S. Gero claims that the letter as we have it is not complete; some sections are missing. The text begins, “You also wrote me about an image of Christ. . .” This could imply that other things were discussed in the letter.[19]19 Since the letter was not included in any of the recognized collections of Eusebius’s works and since the 8th-century iconoclasts were the first to quote it, in a context of controversy, in support of their position, a shadow hangs over its historicity and, thus, over Eusebius’s iconophobic reputation. Is the letter a pure fabrication of the iconoclasts? Is it the work of several authors, of another Eusebius? Did the iconoclasts embellish an authentic text for their own polemical purposes, a text that was less iconophobic than the text we have now, or not at all iconophobic? Is there any other document comparable to this text in patristic literature: a document that, being unknown for 400 years, is brought to light for the first time in a bloody controversy, a document whose implications are so far-reaching and which reverses the previously accepted opinion based on unquestionably authentic documents? If we reject the Letter to Constantia on grounds of inauthenticity or doubtful authenticity, it is difficult to maintain Eusebius’s iconophobic reputation on the basis of his authentic writings.

We must acknowledge that the Fathers of Nicæa II did not ask the question of authenticity even though they questioned other writings that the iconoclasts used to defend their position. They rejected the letter on the grounds of Eusebius’s Arianism, a decidedly weaker argument than inauthenticity. Nicephorus, Patriarch of Constantinople from 806 to 815, in his Contra Eusebium et Epiphanidem accepted the authenticity of the letter while rejecting a letter supposedly written by Epiphanius of Cyprus.

Despite the doubts, there also exist arguments in favor of the letter’s historicity. At the present time, it is probably impossible to prove to everyone’s satisfaction either the authenticity or the inauthenticity of the letter. S. Gero makes a case for its authenticity from the point of view of style, vocabulary, theological context, etc. Our purpose here, however, is to set the letter in the context of all the Eusebian writings so as to draw attention to the deep contradiction between it and the body of authentic, Eusebian writings. This comparison, in our opinion, should lead to an outright rejection of the letter or to a diminution of its importance as a reliable, historical document. As a result, Eusebius’s iconophobic reputation will be eliminated or greatly weakened. In addition, the theory claiming that early Christians were hostile to non-idolatrous, figurative art will be undermined.

Let us set out here the arguments of the two opposing camps:

Those in favor of authenticity:

1. K. Holl[20]20: the style, point of view and understanding agree with those expressed in other Eusebian writings.

2. S. Gero[21]21: similarity between certain stylistic elements in the letter and other Eusebian writings.

3. G. Florovsky, C. von Schönborn[22]22: the Origenistic theological vision of the letter conforms to that presented in authentic writings of Eusebius.

Those who doubt the authenticity:

- C. Murray[23]23: the Letter was unknown for 400 years; its emergence in a controversy; its insulting tone toward an empress is incompatible with Eusebius’s known attitude toward Constantine and his family.

- S. Bigham: conflict between the hostile attitude of the Letter and the positive attitude expressed in authentic Eusebian writings; the contradiction between the existing works of art around 315 and the Letter’s claim that such Christian monuments were nearly nonexistent.

Even after taking into account everything that has been said for and against the authenticity of the Letter, including his own work, R. Grigg had this to say: “Still, I fear that the question of the authenticity of the Letter has not been forthrightly dealt with. e.g., of all these endorsements, only Klauser (n. 7 above) p. 229, ventured to date the letter.”[24]24

A. What images does this text highlight?

If it was written around 315, what does this Letter tells us about Christian images that existed at the time of Eusebius? Not very much since the text is principally theological and not historical. The author, nonetheless, informs us that he took and kept an image that a woman was carrying in her hands. It is not clear whose effigies were on the image: 1) philosophers, 2) portraits of Paul and Christ or 3) Paul and Christ represented with the features of philosophers? The author tells us he had heard of, but had not seen, images of Simon Magus which the Simonians worshiped. St. Irenaeus gives us the same information around the year 190.[25]25 The author himself says he saw an image of Manes, the founder of Manicheanism, carried in processions.

B. What was Eusebius’s attitude toward the images?

What attitude toward images do we see in this Letter? The text leaves no doubt on the subject. The author rejects the image of Christ because, according to him, Christ’s humanity, his flesh, “was mingled with the glory of His divinity so that the mortal part was swallowed up by Life” and, therefore, not representable in a painting. An image of Jesus before the Resurrection and the Ascension is impossible since it would fall under the prohibition of the 2nd Commandment. The letter does not speak of images of the saints; Constantia did not ask for any, but we can suppose that the author would probably have put them under the same 2nd-Commandment ban. The author considers it quite sufficient to “paint” an ethical image of Christ by imitating his virtues.

It is interesting that the author takes a rigorist position regarding the 2nd Commandment. This declaration itself ought to raise doubts about the authenticity of the Letter. Taking into account Eusebius’s preceding texts, of unquestioned authenticity, how can anyone claim that Eusebius maintained a rigorist interpretation of the 2nd Commandment? The statue of the emperor, of Christ and the woman with a hemorrhage, the image of the Hospitality of Abraham (the devil pierced by a lance, Daniel and the lions, and the Good Shepherd that we will study later on) would all seemingly be condemned by such a rigorist interpretation. It is more likely that the Letter, in part or in totality, has been “doctored” because the contradiction with the other Eusebian texts is too flagrant. If we admit the possibility, without any proof, however, that the Letter has some sections missing, what excludes the possibility that other kinds of revisions and alterations may have been carried out? Can we continue to take the Letter seriously in the face of these problems, especially when we compare it to other Eusebian writings?

Notice the question that the author asks at the end of the Letter : “Have you ever heard anything of the kind either yourself in church or from another person? Are not such things banished and excluded from churches all over the world, and is it not common knowledge that such practices are not permitted to us alone?”

The authentic writings of Eusebius’s answer, “Yes.”[26]26 Let us not forget the supposed date of the Letter, between 313 and 324. We already know about Dura-Europos (256). How many other unknown Duras existed in the middle of the 3rd century? What about the catacombs, certain sarcophagi, etc.? Even the Council of Elvira (304) is a witness for the existence of Christian murals. An invocation of a rigorist interpretation of the 2nd Commandment does not stand up in the context of all the other Eusebian writings. This paragraph, at least, has to be rejected as inauthentic. It does not seem to us possible to use this document to establish Eusebius’s attitude toward Christian images.

8. EVIDENCE FROM THE LIFE OF CONSTANTINE

8.1 The Images of Noble, Deceased Pagans: The Life of ConstantineI, 111[27]27

A. What images does this text highlight?

In this chapter, Eusebius does not mention any monuments of Christian art.

B. What was Eusebius’s attitude toward the images?

He, nonetheless, clearly distinguishes between, on the one hand, pagans who want to perpetuate the memory of their noble ancestors in paintings, sculptures and inscriptions and, on the other, Christians who have preserved the memory of Righteous Ones through the writings of the prophets. Constantine is naturally associated with the second group. Without saying so explicitly, Eusebius thinks that he is imitating the Scriptures by writing about the life of a man who, he feels, is not far from the righteousness of the prophets. No painted or sculpted image, no inscription about Constantine is mentioned in this passage. Such a reference would upset the symmetry of Eusebius’s comparison of the two groups:

| 1. pagans | Christians |

| 2. virtuous ancestors | The Righteous of the Old Testament and Constantine |

| 3. paintings, sculptures and inscriptions | Scripture and the Life |

The denigration of visual representations and the valorization of the written word are obvious here. Even though the literary structure is elegant, can we accept this chapter as an indicator of Eusebius’s attitude toward images when we take into account the painted images, the sculptures and the inscriptions about Constantine that Eusebius himself mentions? Is this simply a literary device? As for the monuments of Constantine, Eusebius is not an indifferent witness; he praises either the works themselves or the “intellectual greatness” (III, III, p. 520) of him who ordered them. Here is the point: if this Eusebian text were the only one available on the subject, we would certainly get the impression that he, and probably Constantine also, leaned toward iconophobia and aniconia. An iconophobic interpretation is often given to such statements in other ancient Christian authors. Our evaluation of Eusebius’s attitude is happily balanced by other texts.

8.2 The Image of Constantine and his Children, a Cross and a Dragon: The Life of ConstantineIII, III[28]28

A. What images does this text highlight?

This chapter tells us that Constantine himself ordered, no doubt between 320 and 325, an enormous painting that he set up in public. We can date the order since this chapter, the third of book III, precedes the 6th chapter of the same book in which Eusebius tells about the convocation of the Council of Nicaea in 325. The painting had three levels: the upper level contained a cross; below the cross, in the middle section, were full-length portraits of Constantine and his children—the cross was just above the emperor’s head; on the lower part of the painting, below Constantine’s and the princes’ feet, there was a dragon run through by a lance, falling into the abyss of the sea. The dimensions of the image and the place of exposition, in front of the imperial palace in Constantinople, guaranteed it a widespread reputation. The association of the cross and the imperial family in a painting leaves no ambiguity as to the message: the emperor is on the side of the Christians. He and they defeated the enemy, both political and religious. Eusebius also notes that Constantine consciously wanted “by this allegory” to illustrate a passage of the Old Testament. We have here then the principle that will become classical in the iconodule argumentation of later times: the visible shows what the written word describes, that is, the Gospel message proclaimed in word and image.

B. What was Eusebius’s attitude toward the images?

It is obvious that Eusebius admires and approves of this image. The general tone shows his positive attitude; in his own words, he says that he is “filled with wonder at the intellectual greatness” of him who conceived and ordered such “a true and faithful representation” of a biblical text. Eusebius compares the emperor’s thoughts, “as if by divine inspiration,” to those of the prophets. Consequently, the written works of the prophets and the visible artistic work of Constantine are placed more or less on the same footing. We are very far from the Letter to Constantia in which the author invokes the 2nd Commandment against “any representation of anything that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth.” This chapter is clearly iconophile and opposes any effort to tie an iconophobic tag to Eusebius.

8.3 The Statues of the Good Shepherd and Daniel; the Image of the Cross :The Life of Constantine III, XLIX[29]29

A. What images does this text highlight?

Eusebius tells about the following images that existed in Constantinople: a statue of the Good Shepherd, that is, a symbolic and allegorical image of Christ along with another of Daniel among some lions, that is, an image of a historical, biblical person. Constantine set the statues up in a fountain in the middle of the market place. In addition, the emperor expressly ordered that an immense cross be placed in the middle of the ceiling of the imperial palace. According to Eusebius, it was Constantine’s love for God that motivated him to put the cross on the ceiling, thus, hoping that it would protect the empire.

B. What was Eusebius’s attitude toward the images?

This chapter is of particular importance, coming as it does from a supposed iconophobe, because it shows the distinction between two kinds of images: idolatrous and non-idolatrous. In the preceding chapter, III, XLVIII, Eusebius tells how Constantine, when he founded his new capital, Constantinople, banished idolatry of any kind: no statue that had been worshiped in the temple of a false god, no altar profaned with blood, no burnt sacrifice, no demonic festivity, no other ceremony celebrated by superstitious people were to have a place in Constantinople. Having enumerated what was not to be seen in Constantinople, Eusebius then says, “on the other hand,” here is what can be seen in the city: sculptures of the Good Shepherd and Daniel among the lions. Do we not have here the very principle of Christian iconodulia: the distinction between an idol and a Christian image, that is, an art consecrated to idolatrous worship and an art that has been purified of idolatry and used to proclaim the Gospel? In “Christ’s city,” understood as Constantinople itself or, in the figurative sense, as the Church, symbolic and historical images have their place. And the most surprising thing of all is this: we have this information from Eusebius of Caesarea who, according to the Letter to Constantia, was an iconophobe and an advocate of a rigorist interpretation of the 2nd Commandment.

These two chapters show just how dangerous it can be to interpret a denunciation of pagan worship, including the worship of statues, as a denunciation and a refusal of all kinds of figurative art. According to the advocates of the hostility theory, who claim that the ancient Christians were hostile toward all images, every expression of hostility toward pagan worship, every mockery of idolatrous images, is automatically a refusal of non-idolatrous art. It is highly ironic that it is Eusebius, unconditional iconophobe according to some, who shows us that the first denunciation does not necessarily imply the second.

8.4 The Image of Constantine on Coins and on Palaces :The Life of Constantine IV, XV[30]30

A. What images does this text highlight?

The effigy of Constantine was struck on coins where the emperor was shown with his eyes lifted to heaven as though in prayer. The inhabitants of certain cities placed the portrait of the emperor, painted or in mosaic, on the palace doors of their cities. These images showed Constantine in a praying position, with his hands and eyes raised, but they were not necessarily Christian in content because it was a long-standing practice for the emperor to be represented in this way. Eusebius, nonetheless, thought that such images showed the piety, now Christian, of the emperor.

B. Eusebius’s attitude toward the images.

Eusebius gives the impression of approving the visualization of Constantine’s piety in this sort of portrait.

8.5 The Symbols of the Church in Jerusalem: The Life of Constantine IV, XLV[31]31

A. What images does this text highlight?

This chapter is enigmatic, for it does not make clear the nature of the symbols on the church, symbols that Eusebius wanted to explain through prophetic visions. What was the decoration of the church? Was it abstract symbols, non-figurative, historical scenes, isolated representations or in groups, or composite scenes containing animals and persons? We cannot determine their nature on the basis of this text. On the other hand, the word symbol was used to designate the Good Shepherd and Daniel in chapter III, XLIX of the Life (see 8.3 above). We cannot, therefore, exclude the possibility that the symbols Eusebius commented on at the dedication of the Anastasis Church in Jerusalem were figurative images.

B. What was Eusebius’s attitude toward the images?

Whatever the symbols were, Eusebius seems to have approved them; he shows no sign of protesting their existence. In fact, he seems honored at having been given the privilege of explaining them.

8.6The Image of Constantine in Heaven :The Life of Constantine IV, XLIX[32]32

A. What images does this text highlight?

After the death of Constantine in 337, the authorities in Rome ordered images painted showing the emperor “reposing in an ethereal mansion above the celestial vault.” The content of these images is ambiguous enough to admit a pagan or a Christian interpretation. The great majority of the population in Rome in 337 was no doubt still pagan even though Christians were certainly numerous. The pagans inaugurated the project, but Christians could easily appreciate such images since they did not contradict any Christian truth. In fact, as in the case of the statue of Christ and the woman with a hemorrhage, we have a good example of a development well known in other domains: Christians adopted an imagery that was already well rooted in the pagan tradition and adapted it to their ends. In this case, the image itself could be taken over without any changes; the only thing that had to be done was to give it a Christian interpretation.

B. What was Eusebius’s attitude toward the images?

Before writing this chapter, Eusebius had already gone through the operation of changing the inner meaning. For him, Constantine was a Christian, and the image, therefore, despite the fact that the pagans had ordered it, was seen to be acceptable to Christians.

8.6 Coins Representing Constantine Being Carried up to Heaven :The Life of Constantine IV, LXXIII[33]33

A. What images does this text highlight?

As in the case of 8.4 above, we have coins showing the veiled head of the emperor on one side and Constantine’s going up to heaven in a chariot on the other. A hand descends toward him to welcome him to heaven. What we said for the image of the emperor at rest in 8.6 is applicable in this case also: by adopting this imagery Christians simply gave it a new interpretation.

B. What was Eusebius’s attitude toward the images?

Eusebius expresses no objection to this kind of image.

9. ANALYSIS OF THE DATA

9.1 Summary of the Christian images found in Eusebius’s writings according to section numbers:

| 2, 3 | statues (said to be) of Christ and of the woman with a hemorrhage |

| 2 | painted portraits of Christ, Peter and Paul |

| 4 | a painting of the three mysterious visitors to Abraham |

| 5 | a cross in the hand of Constantine’s statue |

| 5 | a painted portrait either of Christ and Paul or of philosophers |

| 8.2 | a painted portrait of Constantine and his children with a cross and dragon |

| 8.4 | a painted, full-length portrait of Constantine in a praying position |

| 8.6 | a painted portrait of Constantine at rest in heaven |

| 8.3 | a statue of the Good Shepherd |

| 8.3 | a statue of Daniel and the lions |

| 5, 6 | a two-dimensional cross |

| 8.4, 8.6 | coins showing Constantine’s face, his eyes lifted to heaven, and his head covered; the emperor seated on a chariot going up to heaven. |

| 8.5 | unidentified “symbols” |

9.2 The categories of images in this catalogue:

STATUES

- a symbolic image of Christ: the Good Shepherd

- a portrait (said to be) of Christ—a portrait (said to be) of the woman with a hemorrhage

- a portrait of Constantine holding a cross

- a portrait of Daniel among the lions

PAINTINGS

- portraits of Christ

- a portrait of Sts. Peter and Paul

- an image of the three mysterious visitors to Abrahama, portrait of Christ and Paul (perhaps of philosophers)

- portraits of Constantine in various positions

- a portrait of Constantine, his children, a cross, a dragon

BAS-RELIEF

- coins showing Constantine in various positions

PAINTED MURALS OR MOSAICS?

- unidentified “symbols”

As we can see, in his own time, Eusebius provides evidence for the existence of all the categories of images that the Church will know in later times: 1) allegorical personification, 2) portraits, 3) illustrations of biblical texts, 4) historical scenes and 5) signs. Subsequent centuries will only have to develop these categories to arrive at classical iconography as we know it today.

9.3 The fundamental question

The fundamental question which we have tried to answer in our study is this: Was Eusebius of Caesarea really an iconophobe; does he merit his reputation of being hostile to Christian images? After analyzing his writings that refer to images, it seems that the answer is no. He does not deserve his iconophobic reputation. In the end, what does this reputation rest on? On his authentic writings? No. It is based solely on the Letter to Constantia whose authenticity is problematic. Not only the Letter’s entry onto the historical scene 400 years after the date on which it was supposedly written, but also its use by the 8th-century iconoclasts should alert scholars to the problem of authenticity. Its content compared to the authentic Eusebian writings should also sound the alarm. It is only in the Letter that the 2nd Commandment is invoked to condemn figurative art. How can we explain all the other references to figurative art if we accept the notion that Eusebius was iconophobic? The two positions seem to exclude each other, but if we eliminate the Letter by calling its authenticity into question, then there is nothing to explain. A false problem disappears.

Is it possible that Eusebius changed his mind on this question? If we envisage such a change, we must note that the Letter to Constantia, which is the cause of all exegetical problems, dates from the middle of Eusebius’s life, between 302 and 324, according to Wallace-Hadrill. Eusebius must have changed his mind two times, for in the writing at the beginning of his life (first edition of the History, chapters I—VII, The Proof, as well as in an expanded version of the History chapters I—IX) and the writing from the end of his life (The Life of Constantine), Eusebius shows a favorable attitude toward images. The Letter is between the two extremes of his life and requires a double change of mind. Again, it is the Letter that causes a problem, that requires the squaring of a circle.

The contradiction in the data, when it is recognized, causes headaches for the advocates of the hostility theory; even more painful explanations are brought forth to deal with the problem. Klauser[34]34 says Eusebius did change his mind; Baynes,[35]35 after mentioning the statues of Daniel and the Good Shepherd, described in The Life of Constantine, concludes that Eusebius in no way criticizes the emperor’s action, but he says that “it is not necessary to regard this silence as inconsistent with the Letter to the emperor’s sister.” To save Eusebius’s iconophobic reputation, Baynes proposes a distinction between the image of a historical scene and one of an isolated person. According to Baynes, Eusebius would have accepted the first and rejected the second. Bevan[36]36 is also aware of the possible contradiction in the attitudes expressed and proposes two solutions: 1) Eusebius was carried away by his own admiration for Constantine and forgot his real iconophobic attitude when he spoke of Daniel and the Good Shepherd; 2) Eusebius condemned portraits but approved allegories, like the Good Shepherd. However, the 2nd Commandment, as it is invoked in the Letter, excludes both types of images.

The solution to all these exegetical problems seems simple: the Letter to Constantia, as we have it, simply does not have a place in the Eusebian corpus.

We also know that Eusebius admired Origen and that with his master, Pamphilius, he wrote a Defense of Origen. To what point did Eusebius share Origen’s opinions? It is difficult to determine that because the work has been largely lost. George Florovsky thought he saw a current of iconophobic opinion running from Origen through Eusebius to the 8th‑century iconoclasts.[37]37 Although there is an Origenistic flavor in the Letter, why must such a point of view automatically oppose figurative representations? It is true that Origenism devalued history in favor of eternal spiritual values, supposedly discovered in the text by the use of the allegorical method, but the Origenist vision does not deny the reality of history. If the Scriptures which give us a verbal image of historical events are accepted and honored, why must we suppose, without proof, that Origenists are against all forms of figurative art? In fact, a book is the necessary material medium from which flights of allegorical fantasy take off. A painted image plays the same role but in a different medium.

A recent book[38]38 presents an esoteric and Gnostic interpretation of Christianity. By using allegory as a method of interpretation, R. Temple “discovers” his philosophy in the Bible. According to this author, Origen and the masters of the Alexandrian school were among the most honored representatives of this mystical current of thought. Despite his clear depreciation of the historical in favor of the allegorical, Temple claims to see in the Orthodox iconographic tradition another support for his mysticism. He interprets icons in his own way, as he does the Scriptures, to support his religious vision, and he applies the same allegorical method to texts and to paintings. What is surprising, however, is that an Origenist, like Temple, while devaluating the material and historical by exalting the spiritual and immaterial, does not reject icons but rather enthusiastically appropriates them to his own ends. Even though Temple places material things, icons as well as printed books, on an inferior rung of the hierarchy of beings, he sees no necessary contradiction between allegory and figurative art. There, in fact, is none. Placing matter, icons and books on the bottom of the ladder of being is not the same thing as denying them any value and use whatsoever.

10. CONCLUSION

The conclusion is simple: the evidence provided by Eusebius on images shows us someone who has no objection to formulate in their regard. The only sour note in the corpus comes from the Letter to Constantia. If it is inauthentic or if, for other reasons, it is not historically reliable, Eusebius of Caesarea becomes a representative of the emerging iconodulia of the great Church. But even if we consider the Letter as authentic, such as we have it now and despite the problems associated with it, we still have to deal with a confusion and contradiction in the data. Accepting the authenticity of the Letter solves nothing; it only increases the problems. Eusebius cannot be at the same time an iconophobe, as the councils of Hieria and Nicæa II and Patriarch Nicephorus of Constantinople thought, and an iconophile, as St. John of Damascus thought. Finally, only two solutions are possible: 1) exclude the Letter from the Eusebian corpus, and the witness of Eusebius becomes coherent, consistent and iconophile or 2) accept the Letter, and the data becomes contradictory and confused requiring elaborate theories to resolve it. On the basis of the positive data we have from Eusebius on images, it seems difficult to maintain that the Father of Christian historians was an iconophobe.

We choose the simplicity and coherence of the first solution. Long live Occam’s razor.

ANNEX

TEXTS IN TRANSLATION

The numbering is that found in the text.

2. THE STATUE OF CHRIST AND THE WOMAN WITH A HEMORRHAGE: THE HISTORY OF THE CHURCH VII, XVIII3

18. As I have mentioned, this city [Paneas], I do not think I ought to omit a story that deserves to be remembered by those who will follow us. The woman with a hemorrhage, who as we learn from the holy gospels was cured of her trouble by our Savior, was stated to have come from here. Her house was pointed out in the city, and a wonderful memorial of the benefit the Savior conferred upon her was still there. On a tall stone base at the gates of her house stood a bronze statue of a woman, resting on one knee and resembling a suppliant with arms outstretched. Facing this was another of the same material, an upright figure of a man with a double cloak neatly draped over his shoulders and his hand stretched out to the woman. Near his feet on the stone slab grew an exotic plant, which climbed up to the hem of the bronze cloak and served as a remedy for illnesses of every kind. This statue, which was said to resemble the features of Jesus, was still there in my own time, so that I saw it with my own eyes when I resided in the city. It is not at all surprising that Gentiles who long ago received such benefits from our Savior should have expressed their gratitude thus, for the features of His Apostles Paul and Peter, and indeed of Christ Himself, have been preserved in colored portraits which I have examined. How could it be otherwise, when the ancients habitually followed their own Gentile custom of honoring them as saviors in this uninhibited way?

3. AT PANEAS, THE STATUE OF CHRIST AND THE WOMAN WITH A HEMORRHAGE: COMMENTARY ON LUKE 8: 43-487

As for me, I do not think it just to omit a story worthy of being recalled by those who will come after us. In fact, the woman with a hemorrhage was from Paneas, so people said. They point to her house in the city, and there are still admirable monuments to the Savior’s good will toward her. In fact, on a raised stone, in front of the doors of her house, a bronze statue of a woman has been set up. The woman is kneeling on one knee with her hands lifted up; she looks like someone asking for a favor. In front of her is another image of the same material representing a standing man, neatly wearing a cloak and stretching his hand out to the woman. At his feet, on the stele itself, there seems to be growing a strange plant that reaches up to the fringe of the bronze cloak. It is the antidote to all kinds of illnesses. People said that this statue reproduced Jesus’s features and that Maximin added to his own impiety (by destroying it). This is all that is to be said about that. Let us go on now to the following subject.

4. THE IMAGE OF THE THREE VISITORS TO ABRAHAM: THE PROOF OF THE GOSPEL V: 99

And again he adds to this, as if speaking of another: “For I knew that he will establish his children, and his house after him, and they will keep the ways of the Lord, to do righteousness and judgment, so that the Lord will bring on Abraham what things he spake to him.” (Gn 18: 19) The Lord Who answers, Who is recorded to have said this to Abraham, is represented as clearly confessing another Lord to be his Father and the Maker of all things. At least Abraham, who as a prophet has a clear conception of the speaker, prophetically continues with the words: “Wilt thou destroy the righteous man with the wicked, and shall the righteous be as the wicked? If there be fifty righteous in the city, wilt thou destroy them? Wilt thou not spare [all] the place, because of the fifty righteous? Be it far from thee to fulfill this word, and destroy the righteous with the wicked, and that the righteous should be as the wicked. In no way let him that judgeth all the earth, not do judgment.” (Gen. 18:23–25)

I hardly think that this could have been said suitably to angels or to any of God’s ministering spirits. For it could not be regarded as a minor duty to judge all the earth. And he is no angel who is named in the previous passage, but One greater than an angel, the God and Lord who was seen beside the before-mentioned oak with the two angels in human form. Nor can it be thought that Almighty God Himself is meant. For it is impious to suggest that the Divine changes and puts on the shape and form of man. And so it remains for us to own that it is the Word of God who in the preceding passage is regarded as divine: whence the place is even today honored by those who live in the neighborhood as a sacred place in Honor of those who appeared to Abraham, and the terebinth can still be seen there. For they who were entertained by Abraham, as represented in the picture, sit one on each side, and he in the midst surpasses them in Honor. This would be our Lord and Savior, Whom though men knew Him not they worshipped, confirming the Holy Scriptures. He then, thus, in person from the time sowed the seeds of holiness among men, putting on a human form and shape, and revealed to the godly ancestor Abraham Who He was, and showed him the mind of His Father.

5. THE CROSS IN THE HAND OF A STATUE OF CONSTANTINE: THE HISTORY OF THE Church IX, IX, 1011

[Constantine entered Rome in a victory parade after defeating Maxentius, his rival for power in the West] But he, as if he possessed an innate reverence for God, was not in the least excited by their shouts or elated by their plaudits, fully aware that his help came from God: at once he ordered a trophy of the Savior’s Passion to be set up under the hand of his own statue—indeed, he ordered them to place him in the most frequented spot in Rome, holding the sign of the Savior in his right hand and to engrave this inscription in Latin. I reproduce it exactly: “By this saving sign, the true proof of courage, I saved your city from the yoke of the tyrant and set her free; furthermore, I freed the Senate and People of Rome and restored them to their ancient renown and splendor.”

6. CROSS IN THE HAND OF A STATUE OF CONSTANTINE AND ITS INSCRIPTION: THE LIFE OF CONSTANTINE I, XL13

Moreover, by loud proclamations and monumental inscriptions he made known to all men the salutary symbol, setting up this great trophy of victory over his enemies in the midst of the imperial city, and expressly causing it to be engraven in indelible characters, that the salutary symbol was the safeguard of the Roman government and of the entire empire. Accordingly, he immediately ordered a lofty spear in the figure of a cross to be placed beneath the hand of a statue representing himself, in the most frequented part of Rome, and the following inscription to be engraved on it in the Latin language: “By virtue of this salutary sign, which is the true test of valor, I have preserved and liberated your city from the yoke of tyranny. I have also set at liberty the Roman Senate and People, and restored them to their ancient distinction and splendor.”

7. LETTER TO CONSTANTIA16

You also wrote me concerning some supposed image of Christ, which image you wished me to send you. Now what kind of thing is this that you call the image of Christ? I do not know what impelled you to request that an image of Our Savior should be delineated. What sort of image of Christ are you seeking? Is it the true and unalterable one which bears His essential characteristics, or the one which He took up for our sake when He assumed the form of a servant? Granted, He has two forms, even though I do not think that your request has to do with His divine form. Surely then, you are seeking His image as a servant, that of the flesh which He put on for our sake. But that, too, we have been taught, was mingled with the glory of His divinity so that the mortal part was swallowed up by Life. Indeed, it is not surprising that after His ascent to heaven He should have appeared as such, when, while He—the God, Logos—was yet living among men, He changed the form of the servant, and indicating in advance to a chosen band of His disciples the aspect of His Kingdom, He showed on the mount that nature which surpasses the human one—when His face shone like the sun and His garments like light. Who, then, would be able to represent by means of dead colors and inanimate delineations the glistening, flashing radiance of such dignity and glory, when even His superhuman disciples could not bear to behold Him in this guise and fell on their faces, thus admitting that they could not withstand the sight? If, therefore, His incarnate form possessed such power at the time, altered as it was by the divinity dwelling within Him, what need I say of the time when He put off mortality and washed off corruption, when He changed the form of the servant into the glory of the Lord God? How can one paint an image of so wondrous and unattainable a form—if the term form is at all applicable to the divine and spiritual essence—unless, like the unbelieving pagans, one is to represent things that bear no possible resemblance to anything? For they, too, make such idols when they wish to mold the likeness of what they consider to be a god or, as they might say, one of the heroes or anything else of the kind, yet are unable even to approach a resemblance, and so delineate and represent some strange human shapes. Surely, even you will agree that such practices are not lawful for us.

But if you mean to ask of me the image, not of His form transformed into that of God, but that of the mortal flesh before its transformation, can it be that you have forgotten that passage in which God lays down the law that no likeness should be made either of what is in heaven or what is in the earth beneath? Have you ever heard anything of the kind either yourself in church or from another person? Are not such things banished and excluded from churches all over the world, and is it not common knowledge that such practices are not permitted to us alone?

Once—I do not know how—a woman brought me in her hands a picture of two men in the guise of philosophers and let fall the statement that they were Paul and the Savior—I have no means of saying where she had had this from or learned such a thing. With the view that neither she nor others might be given offense, I took it away from her and kept it in my house, as I thought it improper that such things ever be exhibited to others, lest we appear, like idol worshippers, to carry our god around in an image. I note that Paul instructs all of us not to cling any more to things of the flesh; for, he says, though we have known Christ after the flesh, yet now henceforth know we Him no more.

It is said that Simon the sorcerer is worshipped by godless heretics painted in lifeless material. I have also seen myself the man who bears the name of madness [Mani, the founder of Manicheanism] painted on an image and escorted by Manatees. To us, however, such things are forbidden. For in confessing the Lord God, Our Savior, we make ready to see Him as God, and we ourselves cleanse our hearts that we may see Him after we have been cleansed.

8.1 THE IMAGES OF NOBLE, DECEASED PAGANS: THE LIFE OF CONSTANTINE I, 11127

Mankind, devising some consolation for the frail and precarious duration of human life, has thought by the erection of monuments to glorify the memories of their ancestors with immortal honors. Some have employed the vivid delineations and colors of paintings; some have carved statues from lifeless blocks of wood; while others, by engraving their inscriptions deep on tablets and monuments, have thought to transmit the virtues of those whom they honored to perpetual remembrance. All these, indeed, are perishable, and consumed by the lapse of time, being representations of the corruptible body, and not expressing the image of the immortal soul. And yet, these seemed sufficient to those who had no well-grounded hope of happiness after the termination of this mortal life. But God, that God, I say, who is the common Savior of all, having treasured up with himself, for those who love godliness, greater blessings than human thought has conceived, gives the earnest and first fruits of future rewards even here, assuring in some sort immortal hopes to mortal eyes. The ancient oracles of the prophets, delivered to us in the Scripture, declare this; the lives of pious men, who shone in old times with every virtue, bear witness to posterity of the same; and our own days prove it to be true, wherein Constantine, who alone of all that ever wielded the Roman power was the friend of God the Sovereign of all, has appeared to all mankind so clear an example of a godly life.

8.2. THE IMAGE OF CONSTANTINE AND HIS CHILDREN, A CROSS AND A DRAGON: THE LIFEOF CONSTANTINE III, III28

And besides this, he [Constantine] caused to be painted on a lofty tablet, and set up in the front of the portico of his palace, so as to be visible to all, a representation of the salutary sign placed above his head, and below it that hateful and savage adversary of mankind, who by means of the tyranny of the ungodly had wasted the Church of God, falling headlong, under the form of a dragon, to the abyss of destruction. For the sacred oracles in the books of God’s prophets have described him as a dragon and a crooked serpent; and for this reason, the emperor thus publicly displayed a painted resemblance of the dragon beneath his own and his children’s feet, stricken through with a dart, and cast headlong into the depths of the sea.

In this manner, he intended to represent the secret adversary of the human race, and to indicate that he was consigned to the gulf of perdition by virtue of the salutary trophy placed above his head. This allegory, then, was thus conveyed by means of the colors of a picture: and I am filled with wonder at the intellectual greatness of the emperor, who as if by divine inspiration thus expressed what the prophets had foretold concerning this monster, saying that “God would bring his great and strong and terrible sword against the dragon, the flying serpent; and would destroy the dragon that was in the sea.” (Is 27:1) This it was of which the emperor gave a true and faithful representation in the picture above described.

8.3THE STATUES OF THE GOOD SHEPHERD AND DANIEL; THE IMAGE OF THE CROSS: THE LIFE OF CONSTANTINE III, XLIX29

On the other hand, one might see the fountains in the midst of the market place graced with figures representing the Good Shepherd, well known to those who study the sacred oracles, and that of Daniel also with the lions, forged in brass, and resplendent with plates of gold. Indeed, so large a measure of Divine love possessed the emperor’s soul, that in the principal apartment of the imperial palace itself, on a vast tablet displayed in the center of its gold-covered paneled ceiling, he caused the symbol of our Savior’s Passion to be fixed, composed of a variety of precious stones richly in-wrought with gold. This symbol he seemed to have intended to be as it were the safeguard of the empire itself.

8.4. THE IMAGE OF CONSTANTINE ON COINS AND ON PALACES: THE LIFE OF CONSTANTINE IV, XV.30

How deeply his soul was impressed by the power of divine faith may be understood from the circumstance that he directed his likeness to be stamped on the golden coin of the empire with the eyes uplifted as in the posture of prayer to God: and this money became current throughout the Roman world. His portrait also at full length was placed over the entrance gates of the palaces in some cities, the eyes upraised to heaven, and the hands outspread as if in prayer.

8.5. THE SYMBOLS OF THE CHURCH IN JERUSALEM: THE LIFE OF CONSTANTINE IV, XLV.31

I myself too, unworthy as I was of such a privilege, pronounced various public orations in honor of this solemnity, wherein I partly explained by a written description the details of the imperial edifice, and partly endeavored to gather from the prophetic visions apt illustrations of the symbols it displayed. Thus, joyfully was the festival of dedication celebrated in the thirtieth year of our emperor’s reign.

8.6THE IMAGE OF CONSTANTINE IN HEAVEN: THE LIFE OF CONSTANTINE IV, XLIX32 Nor was their [the Romans, Senate and people] sorrow expressed only in words: they also proceeded to honor him, by the dedication of paintings to his memory, with the same respect as before his death. The design of these pictures embodied a representation of heaven itself, and depicted the emperor reposing in an ethereal mansion above the celestial vault.

8.7. COINS REPRESENTING CONSTANTINE BEING CARRIED UP TO HEAVEN: THE LIFE OF CONSTANTINE IV, LXXIII33

A coinage was also struck which bore the following device. On one side appeared the figure of our blessed prince, with the head closely veiled: the reverse exhibited him sitting as a charioteer, drawn by four horses, with a hand stretched downward from above to receive him up to heaven.

S. Bigham, Early Christian Attitudes towards Images, Orthodox Research Institute, Rollinsford, New Hampshire, 2004; as an ebook, google Smashwords and put Bigham into the search engine.

[2]D. S. Wallace-Hadrill, Eusebius of Caesarea, London, 1956.

[3]Eusebius of Caesarea, The History of the Church, G.A. Williamson, tr., Dorset Press, Harmondsworth, England, 1984, pp. 301–302.

[4]John of Damascus, On the Divine Images, Crestwood, NY, St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1980, p. 94.

[5]N. Baynes, “Idolatry and the Early Church,” Byzantine Studies and Other Essays, London, The Athlone Press, 1955, p. 21.

[6]Eusèbe de Césarée, Histoire ecclésiastique VII, XVIII, G. Bardy, tr., (Sources Chrétiennes 41), Paris, Les Éditions du Cerf, 1955, note 1, p. 192.

[7]Eusebius of Caesarea, Commentary on Luke VII, 43, PG 24, col 542-543; the English translation is based on a French one from Greek done by G. Derome, Laval, Quebec.

[8]Sozomenus, The Ecclesiastical History V, 21, The Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, series II, vol. II, Grand Rapids, Michigan, Wm. B. Eerdmans Pub. Co., 1983, pp. 342-343.

[9]Eusebius of Caesarea, The Proof of the Gospel V, 9, W. J. Ferrar, tr., London, Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 1930, pp. 254-254.

[10]L. Thunbery, “Early Christian Interpretations of the Three Angels in Gen. 18,” Studia Patristica VII, 1966, pp. 560-570.

[11]Eusebius, History IX, IX, 10, pp. 370-371.

[12]“Soon accusations spread, as usually happens, because of the proceedings going on, and several incidents occurred. An anonymous document was published containing the names of many persons. Those who denied that they were or had been Christians, when they invoked the gods in words dictated by me, offered prayer with incense and wine to your image, which I had ordered to be brought for this purpose together with statues of the gods, and moreover cursed Christ—none of which those who are really Christians, it is said, can be forced to do—these I thought should be discharged.” Letter of Pliny the Younger to Trajan:

http://faculty.georgetown.edu/jod/texts/pliny.html

[13]Eusebius of Caesarea, The Life of Constantine I, XL, The Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers I, Grand Rapids, Mich. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1986, p. 493.

[14]See the commentary and long bibliography in Quasten, Patrology III, Westminster, Maryland, Christian Classics, Inc., 1990, pp. 319–324.

[15]Life I, XI, pp. 484-485.

[16]PG 20, 1545 ff.; “Letter of Eusebius of Caesarea to Constantia,” Cyril Mango, ed., The Art of the Byzantine Empire 312-1453, Toronto, Ontario, 1986, pp. 16–18.

[17]It is interesting to note that certain modem scholars doubt the authenticity of the Life of Constantine, because it is not found in the list of Eusebius’s works given by St. Jerome only fifty years after Eusebius’s death: H. Grégoire, “La vision de Constantin ‘liquidee,’” Byzantion XIV (1939), note 1, pp. 34–42; W. Setton, Revue des Études anciennes XL (1938), pp. 106–107; P. Petit, « Libanius et la Vita Constantini, » Historic 1 (1950), p. 581. The Letter to Constantia is not found in this list either, and it appeared 400 years after the date on which it was presumably written, in a polemical context. If the Life is doubtful because it is not included in a list after only fifty years, is not the Letter even more doubtful after 400 years? Considering the supposed author, the person to whom he wrote, and the subject, how is it possible that a letter of such importance could have remained unknown for 400 years, then “discovered,” and presented by those who would profit the most by its content?

[18]H. A. Pohlsander, “Constantia,” Ancient Society 24 (1993) note 29, pp. 157-8.

[19]S. Gero, “The True Image of Christ: Eusebius’s Letter to Constantia Reconsidered,” The Journal of Theological Studies XXXII (1981), p. 467.

[20]Holl, “Die Schriften des Epiphanius gegen die Bilderverehrung,” Gesammelte Aufsiitze zur Kirchengeschichte des Osten II, Tubingen, 1928, p. 387.

[21]Gero, “The True Image. . .”

[22]G. Florovsky, “Origen, Eusebius, and the Iconoclastic Controversy,” Church History XIX (1950); C. Von Schönborn, L’icône du Christ, Fribourg, Éditions Universitaires de Fribourg, 1976, pp. 55-85.

C. Murray, “Art and the Early Church,” Journal of Theological Studies 28/4 (Oct. 1977), pp. 326-336.

[24]R. Grigg, “Constantine the Great and the Cult without Images,” Viator 8 (1977), note 179, p. 31.

[25]Irenæus of Lyons, Against Heresies I, XXIII, 4, The Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers I, Grand Rapids, Mich. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1979, p. 348.

[26]The information that archaeology furnishes us makes this question even more bizarre: “There can be no question, then, that illustrations of Christian narrative—put to emblematic use, but including the figure of Christ—were in existence by the middle of the third century. It seems equally clear that their creation expanded tremendously in the interval between that time and the conversion of Constantine.” J. Breckeneridge, « Reception of Art into the Early Church, » Atti del IX Congresso Intenazionale di Archeologia Cristiana I, The Vatican, 1978, p. 366.

[27]Life I, III, p. 482.

[28]Life III, III, p. 520.

[29]Ibid. III, .XLIX, p. 532.

[30]Ibid., IV, XV, p. 544.

[31]Ibid. IV, XLV, p. 552.

[32]Ibid. IV, LXIX, p. 558.

[33]Ibid. IV, LXXIII, p. 559.

[34]T. Klauser, « Ewägungen zur Enstehung der altchristlichen Kunst, » Zeitschrift für Kirchengeschte LXXVI (1965), pp. 5–6.

[35]Baynes, p. 122.

[36]E. Bevan, Holy Images, London, George Allan and Unwin Ltd., 1940.

[37]Florovsky, pp. 77-96.

[38]R. Temple, Icons and the Mystical Origins of Christianity, Longmead, Shaftesbury, Dorset, England, Element Books Limited, 1990.